PANEL 3: Emerging Artists – Shaping The Future

Saturday, September 8th 2018, 4pm - 5.15pm, Liberty Hall, Dublin

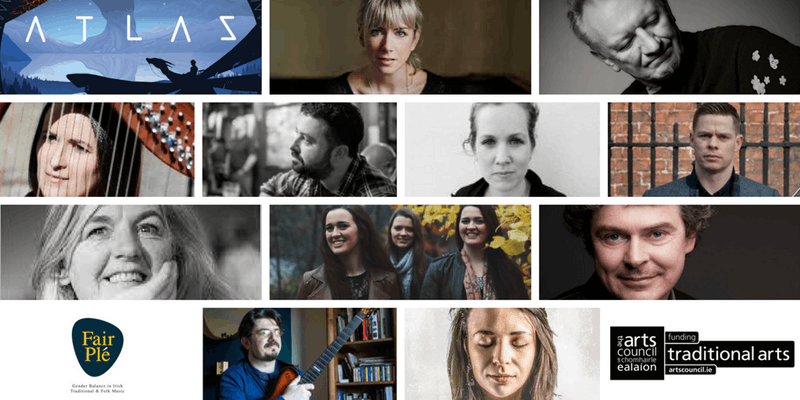

Panellists: Shane Gillen, Muireann Nic Amhlaoibh, Ciara O’Leary Fitzpatrick, Tóla Custy, Nuala O’Connor & Eamon Murray.

Facilitated by Joanne Cusack.

A cursory look at participation in Irish music suggests that equal numbers of boys and girls learn music as children, yet at the level of professional performance, the public face is overwhelmingly male. A panel of experts teased out this issue and offered early career advice to all participating musicians.

Facilitator:

Joanne Cusack is a button accordionist and doctoral researcher from Co. Dublin. Joanne began her doctoral research in Musicology at Maynooth University, focusing her research on gender in Irish traditional music.

Participants:

Éamon Murray is a founding member of supergroup ‘Beoga’ and has worked in all facets of the music industry for almost 2 decades.

Shane Gillen is the director of ‘Big and Bright’ music agency. ‘Big and Bright’ was established in 2017 in response to a gap in the market for an all-encompassing, 360-degree, specialised talent management service and booking agency. Bringing together established industry experience and PR expertise, they allow acts to flourish in all aspects of their careers, presenting greater opportunities for success.

Muireann Nic Amhlaoibh is an award-winning traditional singer and musician from Corca Dhuibhne, West Kerry. She has enjoyed a successful career as a touring artist, with over 13 years’ experience as lead singer and flute-player with the Irish traditional supergroup Danú, as well as performing as a solo artist.

Ciara O' Leary Fitzpatrick, currently head of Digital Marketing at Cork Opera House, has been playing traditional music since the age of four. A concertina player from North Cork, she also is a guest lecturer at CIT Cork School of Music, where she previously graduated from with a Masters in Performance. With music and marketing in her tool belt, she has helped many artists and artistic bodies build their online presence.

Tóla Custy is an exceptional fiddle player and composer from County Clare, who has sought to create a sound of his own whilst remaining sympathetic to the subtle nuances in Irish traditional music.

Nuala O’Connor established Hummingbird Productions with Philip King in 1987 to produce high quality music and arts documentary films. With Philip King, she worked as producer and writer on the BBC’s 'Bringing It All Back Home' and is the author of the book which accompanied the series. Nuala also sits on the governing body of UCC, and has worked as a traditional music reviewer for the Irish Times for many years.

TRANSCRIPT

Joanne: So thanks everyone for coming today, it’s been an amazing day. Personally I’ve had a great experience and feel very enlightened and actually empowered. So just thank you to everybody that spoke already, and particularly Pauline for sharing her story, she is so strong and inspiring. So this panel is going to focus on the transition in music from amateur to professional, and hopefully provide career advice for emerging artists - particularly artists who want to make a career in Irish traditional and folk music.

So, a little bit about myself: my name is Joanne Cusack and I am a button accordion player. I started at the age of nine, and I grew up in Comhaltas and through the competition culture. I went then to Dundalk and I studied music for four years and specialised in performance. I went on to do my Ph.D in gender and Irish traditional music under the supervision of Dr. Daithí Kearney (over there!), and Dr. Adrian Scahill. And I felt the need to study this area because growing up in Irish music, I was surrounded by women in general. I had very little male friends with whom I played music. So when I started to actually want a career in Irish music, I started to think, "Well - where are the female musicians?" You know - because at the concerts, you know, the CDs that are out there, there’s actually very few female musicians represented. And to be honest I didn’t have the confidence and the courage to pursue a career in music full-time. And I think it’s actually very difficult for women in general to pursue a career in music, without actually having another profession. So hopefully today we’re going to talk about the fact that the base of the music industry is predominantly male, and why this is, and then hopefully provide some career advice for people who maybe want to have a full-time career in Irish traditional music..

So I’m going to start with Tóla. Tóla is a fiddle player and composer from Co. Clare, as I’m sure most of the people in this room would know. He has sought to create a sound of his own, whilst remaining sympathetic to the subtle nuances of Irish traditional music.

Tóla: How ye doin’. I’m so proud of today, I really am. I’m so proud of a crowd that can get together and ask questions; I think that’s the most important thing about today. And what was really eye-opening for me over the last few months - before I talk about what I’m supposed to talk about - is the assumptions that were thrown at me what they thought this was about – "Oh, you want to name and shame, don’t you" ... "Oh, you want to go around and identify certain things that are wrong". And I’d be going "Where did you read that, have you actually been on the site?" Where I’d actually stop in my own area and go "I’m not actually going to discuss this because I know you actually haven’t looked it up, and until you do, I’m not talking to you about it." Because I think the best thing a society can do, and look it, we’re musicians but we’re also part of a larger society here, and I don’t think….. I’ve always loved history, but I don’t think there’s ever been a perfect society - there’s never been Utopia. There’s … the best of societies look at themselves consistently and ask questions, and aren’t afraid of the answers. And I think if you start from that perspective in a society, you’ve some chance of actually progressing.

So, I come from Co. Clare. I guess I was lucky, two ways, musically and genetically, in the sense that – I was… my Dad and my Mam came on music really late, so that they had no preconceptions to what music was, so for all of my family it was a wide open door, so that there was never … all they wanted was exploration, really, it didn’t really matter, there was instruments everywhere. So when it came to my own personal exploration, I kind of had kind of had nobody jumping on me shoulders. So that was actually a luxury, I really find, because I used to see it with other people and they had so many monkeys on their back when it came to their own sense of self, I guess. So I had that. The second thing which is probably in context today – I have four older sisters. So this was, this situation I suppose, was kind of in my household a lot earlier maybe than a lot of other households. So … and because I had older musician sisters going out there into the world, I became aware of … again I mentioned it earlier, that funny 'wink-and-elbow' stuff that you see, again in our wider society - you see it’s not just music, it's everywhere. And so I was always aware of that, and I suppose I was conscious that, you know, that I would like to not be like that, I guess.

So I think I’m here today to talk really about the music and where to go. And I work a lot in U.L. and again it’s amazing that, I don’t know what the numbers are, but predominantly, especially with fiddle, you know, it'll be majority girls that I would be teaching, especially in the B.A., and you know I’m doing this about 10 or 12 years, on and off in U.L., and where that translates is not that, you know and I think it was Dermot that asked that question, you know, and it’s so true. And I have no answers but everybody comes up to me asking "What’s the story with FairPlé?" - that’s what as I always give as my answer. I want an answer to that. I have no answer myself but I certainly am happy to ask that question, and explore it - because I think it’s part of a wider … so I come from a primary school teaching world as well, so I think our biggest problem still as a society is the 'warrior versus the princess' mentality, and that’s it in its most obvious way. Whereas our boys are still raised to be warriors and our girls are slightly encouraged to be princess-like, you know, you follow either Conor McGregor or you follow Kim Kardashian. Both sides are dangerous as far as I can see, and I’ve got to say this too while I’m at it, there is a fine crowd here today but there are tens of thousands watching and waiting and listening, believe you me. So if the people involved at the higher levels in this need encouragement, there’s your encouragement, keep saying what you’re saying, keep saying it in the lovely way you’re saying it, because all I’ve ever heard in any soundbite I’ve heard from anybody that’s represented this grouping, is that you want to ask questions. And anybody who doesn’t want to sit in a room where questions are asked, really is of no benefit to society whatsoever, in any situation, you know.

So what is this animal that we call music? I’m not sure, but it’s the one activity that has me jumping out of bed no matter how tired I am. And I try and inject that enthusiasm into anything I do. And I think the hardest thing for an emerging musician, a younger person when they do this, is ... it’s something that I learnt an awful long time ago, which was to not think about the other musician in the audience, to think about the non-musician. To think about the man or woman who knows nothing - what do they need? Because what they need, is entirely different to what a musician sitting in an audience needs - and who pays in? So in that sense, I always work around one word, which helps me when I’m working out, or in collaboration in a group situation, which is clarity. You have to have clarity first of all, of a vision; sometimes you have to put words on something before you actually can put music to it. Half of the collaborations that I’ve really enjoyed and gotten extreme meatiness out of, have been the collaborations where we’ve sat around and actually put words and sentences together of our objectives. And it’s dangerous, it’s awful, it’s excruciating, because all you want to do is play, because that’s your job. But sometimes you need a vision, you need a word, I’m about to work with somebody soon, and listen to this for a sentence that has us inspired – ‘I charm what I can from the quiet’. I mean, like, if you can’t work after that, if it doesn’t just make you jump out of bed and take a quick shower and open up your instrument case then I don’t know what won’t. But I always say that to students and to people who are trying to get a craft. So - that’s the first thing, clarity.

And then that translates into clarity of phrase, clarity of choice of melody, clarity of ... again, how am I making this clear to the person who knows nothing? But I need that person to leave and feel that they were just as involved. Because the most dangerous thing as musicians, or as singers, or as performers, is that if it goes over that person’s head, then you’ve lost - you might as well play in your own kitchen. So that’s another thing, the clarity of …. what I mean is the situations that I’ve seen where it doesn’t work, is when you’re hearing the music … "Hey Ma, look, no hands!", because you’re forgetting about the animal that you’re trying to show everybody, which is that piece of melody or that song or that moment of emotion, which is the third thing, the clarity of emotion. That is extremely… they have to taste an emotion from what you’re giving, it’s really, really important. And you see, look at all we just said there, doesn’t that tie into anything that you do generally in society? You know if you’re in a collaborative situation or in a work situation, the most important thing is that everybody feels that they have something to contribute. Now as musicians, and most of us are musicians here in the audience, I mean we’ve all been in situations where that has broken down, detrimentally, you know where a group, or a number of people or one person decides to be the boss, and they’re just excruciating situations. So as a younger person, and I’m speaking to those, because that’s kind of our remit here, you know - don’t be in a situation like that, leave it. I’ve done it, it’s really important. Because you’ll feel an awful lot healthier and you’ll sleep a lot better. And you will actually be a better person and a stronger person for the next situation you go into, because something happens when you allow it to fester and not be part of what you need as a human being. And it moves into lovely places if you get those collaborative situations when you feel everybody is contributing. And it will come out in the performance, it will come out in what you develop, in your material. I think it’s really, really, really, really important.

I’m about to finish, it’s been very quick. Except to say that, you know, the second thing that I really - you need to know as a younger person in this, is…. it was a piece of advice given to me an awful long time ago, by a girl in New Zealand, in Christchurch, years and years and years ago, a whistle player, and I’ll never forget it. She was slightly bemoaning the fact that she played Irish music - here we go - but had never been to Ireland but she said the following, that I’ve never forgotten, and it’s a philosophy which I try to follow because you can apply it to anything, which is the following – she said, "I’ve never been to Ireland, I feel really bad" but then she said "Well, when I hear it, it’s Irish, but when I play it, it’s mine.". Well done today, thanks a million.

Joanne: Thanks Tóla, that was great.

Éamon Murray, I’m going to go you to next, he’s a founder member of supergroup Beoga, which we all know because he has worked in all facets of the music industry for almost 2 decades. So - Éamon!

Éamon Murray: I feel very, very proud to be this woman’s husband. She’s been travelling with us for the last few weeks, and just the tone today was perfect. I suppose being in a band with another founding member of FairPlé, it all came at a time - for me anyway - that I just started noticing, Pauline was teasing out the conversation out of me, and because I won the gender lottery I never thought of it. There she is now, watch her! So, being in a band with Niamh as well, another founder member, and when the conversation started happening about FairPlé I just realised that I had never thought about it. I mean, I’m the only boy in the house with three sisters, and I was always brought up with an inherent sense of fairness, but I never really looked around in the music business, say, to see was it a problem and then as the conversations … it just became more and more obvious as the conversation went on. And it was also a time when they were kicking off, that we, you know, just started getting managed by a woman called Sarah Casey, who’s a 30-year old woman from Mayo living in London, and a really, really bright spark in the business, she just knows it inside out, and she and I would have been going to meetings with these middle-aged white music executives from big labels who have controlled massive labels worth hundreds of millions of dollars. And there would be just be the three of us or maybe four of us sitting in a conversation, myself and Sarah at one side, and these label people, and Sarah would ask a question, and the label people would look at me and answer Sarah’s question to me, and Sarah would ask another one, and the same thing would keep happening, you know? And I think I would have let it pass only for the FairPlé and the #MeToo and the whole tone in the time that we’re living in. I just kind of looked at Sarah then if she was asking the questions, and eventually by the end of the meeting the lads realised "Oh, we’re talking to the wrong person.". You know, subtle little things that happen every day, we had a few this week. We’ve just come back from a week of recording in England and subtle things I would say that I wouldn’t have noticed, and I know that Niamh is appreciative now that we are starting to notice and that the conversation is starting to shift and it’s that gradual thing that, I think it's awareness that, as Tóla says, is being spread way beyond the people in this room, when I think it’s just small incremental steps it just changes the overall climate. You’re absolutely rattling, you’re rattling all the right keys, fair play to you.

So I – in terms of the "Emerging Artist" advice, I don’t – I think if anybody says that they know the formula, then they’re talking shite to be honest, because I think it’s a lot of things. If I could go back, and change anything in coming in to music, I would have better equipped myself I think with skills. If you’re prepared to do the 90% of the admin and all the other stuff, then you’re probably be fit to make a living out of music in some shape or form, because all of that just gets really … you get bogged down in that, and I sort of regret not having, you know, not being able to edit my own videos, and not being able to edit my own music, and not being able to be really good at the back-end of social media and not being able to code, and not being able to do all these other skills that you need in order to go and actually play music. So I kind-of wish that I had done that and if I was encouraging my own daughter to get into the music business, it would be, I don’t know I suppose, equip them with all the other skills that you need to kind of go ahead and do that. That’s really my career advice. I’m looking at all of ye here like – "We don’t need career advice – what the hell was that for?!".

I mean in terms of Irish music, I think we’ve got a lot of challenges ahead in the genre. We were lucky enough, we won the lottery in terms of that as well - in that we got a touch from Ed Sheeran and somebody like that is, you know, you could dream of somebody like that writing an album for Irish music, but we’re very good at boxing up and selling our indigenous product in a certain way, and framing it in a certain way that’s supposed to be good you know. We can box it up and show the people ‘Look here you go, this is what we can do’. Or the dance shows that seem to kind of going and going and going and going, and the music … I suppose the stuff that cuts through is – the perception that fast is good, you know, that four on the floor and everybody clapping is … If you put bass and drums underneath that then you can go and headline all the festivals you know, in America and you can do all that - and then I think people can kind of get into the rut of making music just to be on the road, or you make an album just because … ‘Oh I was in that country last year so I’d better make an album so I’ll sell a whole load of them’ and you kind of end up putting the cart before the horse, a wee bit. And I think it’s going to take a bit of a shift in our thinking about what’s good, and what’s not. I think we need to champion a bit more stuff that’s maybe left of centre, or that's kind of encouraging a bit more creativity, so young ones coming out of the college don’t think, "Well if I’m going to make any money I need to go and play the fast stuff and I need to go and play it with bass and drums underneath it and then I can do those festivals in America" or "I need to go and learn how to play two or three things at the same time and I’ll get on to a dance show" you know. It seems to me anyway, the wrong way of coming about playing the music that you want to play - that should be the first thing, and I think if the rest of us … to go back, we touched on the radio thing, that if it was being championed a bit more just in society, that there’s more options than just the hard and fast ‘four on the floor’ - that I think it would go a lot further, and I think it would encourage a lot more young people to kind-of get in and just play the music that they want to play, if that makes any sense at all. And that’s me - sin é.

Joanne: Thanks Éamon. So next we have Shane Gillen, he’s the Director of "Big and Bright" music agency. "Big and Bright" was established in 2017 in response to a gap in the market for an all-encompassing, 360-degree, specialised talent management service and booking agency. So Shane …

Shane Gillen: Hello, firstly I feel very un-talented because I am the one who pays … I can’t play any instrument, so I would say I’m very much in the minimal margin in the room. But I do work in the music industry, my name is Shane Gillen and yeah I set up a company called "Big and Bright" last year. (I feel like I’m being shunned, I can’t play anything - I can play Wonderwall!) So I think you’re all incredible, and I think today is really special, certainly what Éamon was saying as well about rattling cages - I was just listening to Hozier’s new EP and you know his whole thing is about… (I know he was at ‘Stand for Truth’ a few weeks ago) but there’s something about those grassroots movements, certainly in the last five years in Ireland, that actually seemed to kind of have a cause and effect, I feel like. Certainly the last talk, I was sitting out in the hall for it, but it’s just really refreshing to even hear some of that stuff being discussed, you know, certainly by younger people as well, talking about this kind of thing.

So I decided I’m going to tell you a little bit about how I’m in the music industry and where I’m at. We manage a band called … I’ll give you a case study of kind-of our biggest act is Chasing Abbey. They’re Irish pop, do you know there’s probably not that many teenyboppers in the room but they’re very much a teenybopper kind of band. They’re three guys from Tullamore and they were a trad band actually, which you might not believe if you were to hear their songs because they rap now and run around the stage doing rap music now. But Chasing Abbey started as a band called Rugged Wood, violins and double bass, all of that, there was five of them. And they won a "Battle of the Bands" competition in their school in Tullamore when they were all aged 15 or so, and that’s when I first saw them. They would have been in first or second year in school and I went to that school in Tullamore for a while and I remember going – they had launched a new hall, very, very local colloquial thing, and they were launching a new hall and I was there for the launch of the new hall, invited back to my old school, and the band played and I was like, these guys are unbelievable. And it was at the time when you know Mumford and Sons were all over the charts, and now there’s these young 15 year olds doing trad sort of Rhianna, and it was really, really cool, and they were really young.

And I kind of just kept an eye on them. I worked in the entertainment business myself, and you know I kind of thought they were going to be amazing and maybe in years to come I can probably help them and I might have friends, you know the way you kind-of think… I’m also acutely aware of the title of the talk, and the kind of construct of the room where we’re on a stage, and we’re giving advice and like, who are we to give advice as much as anyone else is in the room? So I’m really aware like, as Éamon says there is no … - anyone who says they can just say "Here’s the formula", I think is talking shite. But I thought that maybe I can help this band in years to come, but firstly they have to go through school. So they went through school and coming up to the age, like they were around 17 or 18, I started getting them gigs just through friends of mine, and sort of around bars, like you know how it is, you know small gigs, and small gigs lead to bigger gigs, and all this networking. I gave one of them grinds actually for his Leaving Cert., and I really ended getting really invested in these guys, in Rugged Wood and they released a song called Warmth, and it went up to the top of the iTunes charts and at the time I was like ‘Woah this is going to be huge’ and nothing really came of that. Anyway, two of the guys left the band and they now had three members and they told me that they wanted to turn into a rap group from Tullamore. So I was like "No, you’re not doing that!" They were like, "We’re getting rid of the instruments and we want to become a rap pop group because that’s what we listen to.". And I’m 100% - like I remember thinking "This is not happening!' like, you know. But also your job, your duty as someone who’s helping any artist is to let them develop, you know, so of course I didn’t say that to them. And they sent me a song, and I was like – "OK... " They sent me a song, there was no instruments, you know they’d made it all on the laptop. And, yeah, it was interesting, and this was the new route that they were exploring and I was getting married in Paris and I told them that their first gig, as their new rendition of whatever it is, was going to be at my wedding, right? So I told them to get together for that, like get themselves ready for that. So they came up with the name … I gave them a book on Theatre Studies as well, I had done a lot of theatre work and in the preface of the book, the author was talking about how your first move as an actor going on stage is to cast your audience, and they kind of took that really literally, and they decided that their audience was a fictitious person named Abbey. They write everything for Abbey and at the time Abbey didn’t exist, so they were chasing Abbey, so that’s where the name came from. It’s actually really, really deep like, you know – for a Tullamore rap group! - Or T-More as they call it! So anyway – so they, in fairness got themselves together, came to France, they got steamed drunk and they went on stage and performed as Chasing Abbey and everyone was like – everyone was talking about them! Obviously we were all fairly hammered but everyone was like "These guys are unbelievable." Actually I remember an English friend of mine there, Garry is his name, he turned around to me and he was like, "Aw, you're going to be the Irish Louis Walsh, mate!" And I was like - "Louis Walsh IS Irish." I’ll never forget he said that. But anyway, one of my best mates was at my wedding as well, obviously, and he worked in Edelman PR, which is one of the biggest PR companies in the world - Greg is his name. And Greg started telling me, you know, late night conversations, "Oh I can get them on Spin, and I can get them on ... " you know, and all this stuff. I started thinking, maybe I can work with them, as this new rendition, as 'Chasing Abbey'. So, we decided we’d give it a go, and in fairness, stood up to anyone who was like … - and there was a lot, and there still is a lot - of people who are like, "What are you doing? You’re three young lads from Tullamore, you can’t do that music." And people don’t know that they actually have a really established background in music, they’re all incredible musicians, they play about … they’re multi-instrumentalists, they play like 6 instruments each, all of them, so it’s really interesting that they come from that. And they’ve also brought the banjo with them into Chasing Abbey, so every rap song that they have has a banjo with an obscene pedal board, and all these effects on it, but it's still a banjo - so they wanted to bring some of that.

Anyway, long story short, they wrote a song called "That Good Thing" and I remember being in the car with my wife at Christmas, two Christmases ago, and they sent it. And again I was like "What’s this?" But anyway - we submitted it to Today FM, there was a competition on Today FM for – it was the Louise Duffy show and they were looking for emerging – they were looking for new Irish artists. And we submitted the song and they were going to select one song, and they were going to playlist the song, so that was kind-of the prize. And we submitted the song, it’s one of those things, I don’t even remember sending the email, you know the way, it’s just – it was a nothing moment. And we got an email back two weeks later saying that "You’ve won", like, and "That song is going to playlisted.". And like this, like, you know, "What?" It was just madness to me like, and it was such an early song and the guys, even the guys would look back and "Ooh it’s a little bit, you know..." - it was the first song, it was the first song they ever wrote really, and it got playlisted, and then really suddenly became the most "Shazam"-ed song in the country and we ... There was nowhere for anyone even to get it, it wasn’t on Spotify or iTunes or anything. And it was at that moment that we got ourselves a music lawyer, Willie Ryan, probably loads of people know him, you know, he’s everyone’s lawyer. Willie rang me and was like "You need to get yourselves together" because basically we were chasing our tail, I was just someone who was helping the guys, and just kind of decided, right, I’m going to give this a go, and obviously had lots of doubts, read every music business book. Again, there’s no formula but I attended all the talks, read all the books and was like "OK, can I do this?" There was a lot of that. So we released the song, within 24 hours it went to No. 1 on the iTunes charts. Within another 24 hours Willie was calling us saying that there was a record deal on the table. And then there were 6 record deals on the table. So we ended meeting every major – me going into these meetings - every major record label in the UK: Atlantic, Polydore, Parlophone, Warner, Universal. Yeah, we sat with them all. No women, in any of those meetings, which obviously when I signed up to do FairPlé I just started thinking of our last year, and I started thinking of the amount of women that I’ve met in the music industry over the last year. And I’ve met loads of people in the music industry over the last year, and I think … I can probably count them on one hand. And yeah - and it’s sort of this male, sort of self-aggrandising industry, and I totally see that, for sure. Yeah so we went, we signed with Universal, and somehow that song got "Song of the Year", RTÉ Choice "Song of the Year". I’ll never forget listening to it in the car, being like "What the fuck is this?" It also goes to show that actually you need to listen to … certainly I need to listen to what their fans like, you know what I mean. When Chasing Abbey now write stuff - and they’re constantly writing stuff and sending it to me - I don’t - if I don’t like it, I don’t say - like, I just know it’s not for me. I’m not Abbey, you know what I mean, so… I’m just not, I’m not Abbey and they’re not writing it for me. And they’re really acutely aware of who their audience is, so, and it’s worked, so it works really well for them.

So over the last year we set up "Big and Bright" as a result of them getting the record deal. And I suppose the onus on us is to guide three young guys through a fairly murky industry which is full of people who will lie, and let you down, and treat you really badly, and you know, even your relationship with the label, you go through the honeymoon phase at the start and then, you know, you’re fighting all the time. I remember reading a thing once about music management, and I heard that someone said that, "In music management, every win is theirs and every loss is ours". So we'll take the losses and they can have the wins. And you just have to you know, be ok with that, as someone who… you know you have to just take those losses, and we’ve had major losses, of course we have.

So I guess our challenge going forward - and I don’t know the formula! - is to guide these three young guys through an industry without messing up their lives, you know? It’s a huge burden of trust, and yeah, so that’s kind-of where we’re coming from, myself and Greg. We’ve a good few other clients as well but they’re kind of our case study. We actually … yeah we signed a publishing deal with – are you guys with B-Unique as well? I think you are … Yeah we signed a publishing deal with B-Unique as well. Yeah so they’ve just … yeah they’ve released three songs, and that’s Chasing Abbey, and that’s kind of where I come from, and that’s kind-of my story I guess.

Joanne: Thanks Shane for that insight into the music industry. It’s nice actually to be able to get an insight into that side of things.

So Nuala, I’m going to come to you next. Nuala O’Connor established Hummingbird Productions with Philip King in 1987 to produce high quality music and arts documentary films. With Philip King, she also worked as a producer and writer on the BBC's ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ and also wrote the book that accompanied that series, later. She also sits on the governing body of UCC, and is a reviewer for the Irish Times.

Nuala: That’s a slightly out of date C.V. in fact, but it's true. So I just want to thank you, Karan, for the invitation to talk here, and it's just lovely to be in a room like this with - to be able to talk freely - and amongst most people that a lot of you have met, know well and regard as friends. And I’m talking from a vantage point which is 28 years since we made ‘Bringing It All Back Home’, and longer than that, I think another 10 years, I worked in RTÉ as a radio producer and a television researcher, sometimes involved with music productions and sometimes not. So I’ve seen it all, really, in that before I even went to RTÉ I was involved. I was a founder member of the Dublin Folk Festival with Conor Byrne’s mother, Eilish - and I would often ... we laboured long and hard at "The Meeting Place" and other folk and traditional clubs where you could barely make out the musicians, for the amount of cigarette smoke in the places. I mean it’s … I just sometimes pinch myself and think am I ... because I still think I’m 24! ... has this all actually happened? So I think back in the time when I started out, that traditional music as an occupation - if we just get rid of the professional / amateur sort of labels - was a low-status occupation, by and large. I remember when I was in Trinity, going back even further, I was involved in Éigse na Tríonóide, the first ever traditional folk festival that happened in Trinity, and we had a pipers concert in the Junior Common room, and I remember, I think it was Ciarán MacMathúna came out of that concert and said, you know, "I can’t believe that you filled a room with people who knew nothing about pipes or piping or anything, to listen to five pipers on a Tuesday night in March" or something like that. So it’s come a long way. And I think at the heart of it, in terms of women, I just did a little exercise where I wrote down all the of the names of all of the people that we had filmed in performance in ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ and fortunately I have a good memory and I got to 82, which I think is pretty representative because we shot 57 hours of music for that series, and by the way it is a series that could never, ever happen today. No public broadcaster would commission it, and it cost about 1 million pounds sterling to make. We had multi-track recording OB, we had every bell and whistle that was available. Plus the book that was mentioned, was published by BBC Books, I mean the idea of anybody publishing a book like that nowadays would be also I think, just – they’d laugh you out the door. And we were free to do everything like that, from film two old men, the Killury Brothers down in west Clare, dancing on their flag, Liscannor flag kitchen, or rather playing for a dancer, right up to the Evan Brothers in Nashville. It was fantastic. As a first project in independent television production it was a ridiculous idea, because nothing like that ever happened again. Everything after that was very hard-won.

But anyway, of this 82 people, men and women ... in my memory, if you’d asked me how many women were involved, I would have said "Oh I’d say 50/50, 40/60 maybe?" I remember the women, all - I remember every single session with the women, I remember all of the sessions but the women stand out. Well I find I have actually 22 women, and I was completely shocked. It really, really set me back on my heels. But of those women, every single one of them is still in the business. So we - the youngest of them might have been in their early 20s, somebody like Sharon Shannon was in ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ I think she was 22 at the time, certainly very, very young. And then there was a group of women, Mary Black, Maura O’Connell, Moya Brennan, Dolores Keane, and … who would have been maybe 10 years into their careers, which were then even stellar at that stage, everybody knew who they were, and everybody still knows who they are. And then people like Jean Ritchie, who has since died, who was an old woman when we filmed her, I think she was in her late 70s, and died last year, I think it was, well into her 90s. But I think what I’m saying is, that the good news is, that the life cycle of a traditional player, man or woman, is long. And that isn’t necessarily the case for the very competitive kind-of "pop" end of the music business. One reason why perhaps it’s so viciously, you know, competitive and exploitative actually is because the people in it are so young. And that’s the good news. The bad news I suppose is that audiences are aging, and if you’re looking to your audiences, and bearing in mind what Tóla is saying and somebody mentioned earlier, we need to some more work with radio and television, and just to give you a really horrendous statistic - which is the only one I’ll give - is that the average age of the listener, of listeners to Radio 1 right now is 60. Now that’s only going one way. So the challenge is to be very creative about creating an audience and you can have a kind of ... a bit of an illusory effect in traditional and folk music because it is both a profession and an occupation. By the way the traditional - the Arts Council report on the traditional arts which kind-of established a framework of support for Traditional Arts Performance - has explicitly said that they would not use the term "amateur", that it had no meaning in traditional music, because as you all know, and as people have cited, there are people who will appear on, if you like, commercial performances, in that money is charged for tickets, but those people could play with professional full-time musicians who are earning their entire living from the practice of traditional and/or folk music - but they are people who may appear or even play or collaborate with them are not full-time professional traditional musicians. So it’s a very unusual profile I think, the traditional and folk musician. So advice for young people, again there’s no formula and nobody knows anything. that’s the other thing, nobody knows who - who would have thought that those boys from Tullamore would actually have the success that they’ve had? And that’s been the same forever and ever amen. And so… what I’m trying to say is hang on to your creativity. Don’t let anybody mess with that because even though it can be grim, it can be really grim, and I’m not saying that … it is no recipe for success or anything like that, but you’re going nowhere if you do what Éamon describes, the ‘four on the floor’ thing, I’ve seen it all and they’ve disappeared into the woodwork, and never to re-emerge. But if, and I think this is perhaps an area where traditional music can be faulted, I mean we’ve all heard the term ‘folk police’ and all the rest of it, there is a sort of ... this is the problem with our traditional music, it has a strong conservative undercurrent. It is necessary to keep it like that, and there are people at the heart of that, who maintain it like that, and that’s very important, otherwise the whole thing could completely just become adulterated to the point where it’s not recognisable any more. But there are things happening, usually at the margins, and usually the people who do it are either just blind to the fact that they’re going to bring coals down on their heads by doing what they’re doing, or they don’t know that they’re doing it! Like a good example – because it’s not Irish I think I can say it, we made a film with The Gloaming, and Thomas Bartlett said "I just did what I wanted because I didn’t know what the rules were. So I liked the way the music was, and I liked what I was doing with it, but I didn’t know that there were rules about what you could or couldn’t do, so I didn’t know I was breaking any rules!" But that’s a very happy position to be in, and not everybody can be there. So I think - be creative, and hang on to what you feel. And again what Tóla was saying, you have to connect with your audience. And that does not mean that when they yell up a tune that they want to hear, "Danny Boy" or whatever it is, that you just feed them whatever it is they’re - if they want something that you can’t give, you can’t give it. But be brave, and by the fourth or fifth time you’ve done it, they’ll like it! Because it’s you, it’s from you, it’s creative, it comes out of your … So it’s not enough just to be technically competent and do the ‘Look Ma, no hands’, I’ve seen so many musicians who can do that, young musicians who think that that’s actually a cool thing to do, and I suppose when you’re 15 it is a cool thing to do, but you have to go beyond that.

In terms of women, and this issue … that 22 women they represent maybe … my percentages aren’t probably good, but it looks like they’re coming around 20/25% . Now that’s a figure that’s kind of being bandied about here a bit, in terms of … it’s come up again and again here as a kind of – it’s like Pi R-squared, like a constant. Because I then decided I’d look at ‘Sé Mo Laoch’ which was a series that I was involved in for five series of six programmes each, from about 2002, I think … to ... and it’s still running but I’m not involved in it any more. So I counted up 30 artists that I had personally – I had either shot the programmes and/or edited them, and I got 6 women and 24 men. And that’s the same, that’s about the same percentage, but this is running up to much later, to maybe 2010 when I did the last one. So that hasn’t changed at all. And the interesting thing that I noticed about the women, I’ll tell you their names because there’s only six of them, Treasa Nic Llafferty, Treasa Ní Mhiolláin, Josephine Keegan, Sarah Ann O’Neill, Kitty Hayes and Máire Ní Cheocháin and four of them are singers, and there isn’t the same percentage of singers in the men. And I don’t know what … why that should be, is it that singing women had more of an opportunity ... they stayed singing ... and they sang, they could sing all the time so they could practice their art all the time with ... they didn’t need an instrument. Kitty Hayes, now, Tóla will have known Kitty. She’s a really interesting woman and I just absolutely loved Kitty, because when we met Kitty, she had taken up the concertina after a break of, I think, 45 years. She had married a man who was a very well-known flute player just outside Miltown Malbay, a friend of Willie Clancy’s, played in the céilí band there, Tóla will remember it I’m sure. But anyway -so she had reared six children, she loved farming, she never owned a concertina, she never … she – even before she married, she never owned a concertina. When she was married sometime in the '60s, they went on a trip down to Kilrush and they called into the famous Mrs. Crotty, and her husband and Willie and Mrs. Crotty played in that famous back room in the pub in Crotty’s there, and did Kitty even say that she played the concertina, that she knew a tune, … did she ask Mrs. Crotty for the loan of a concertina? She did not. She went away from there and she never… and Mrs. Crotty was none the wiser that this woman played the concertina. Moving quickly along, her husband died, her eldest son died tragically, and before he died, he was very ill, and to amuse him, she borrowed a concertina and used to play for him when he was ill, and he said "When I die - " I mean it’s a terribly sad story, but - "When I die, you must keep playing." And so she went into Custy’s in Ennis for about a year and took down every concertina in the shop, and tried it out, much to Eoin O’Neill’s amazement, and he ended up - she bought a concertina, and he ended up playing with her, and then she ended up gigging five nights a week. So her children were ringing her up, ‘Where’s Mammy?" "Oh she’s out in The Old Ground tonight, oh she’s down in Coore tonight" or whatever it is. She disappeared, she just disappeared out into the world of semi-professional, you could call it, but she was paid for some of these gigs. She recorded three albums, she died at 82, having had 12 years semi-professional life as a traditional musician in Clare. And she said to me "Some people say life begins at 40, but for me it began at 70!". I always think about Kitty, and think like, just hang on in there. You know it’s - I’m not saying to wait until you’re 70, but it’s a world of full … weirdl, it’s a very difficult world to make your way in, and clearly the women issue is … there seems to be some kind of learned invisibility in there, is what I’m trying to say about that so that. (Now I think that was sometimes mirrored by the men as well who felt that maybe traditional music was something that they did not do professionally, certainly and certainly I’m thinking here of … Chris Droney told me that he was music mad when he was a teenager, but he also had to help on the farm, he was needed by his father and that one day he took a break and he went upstairs, because this tune was annoying him, and he went upstairs, into the bedroom and he was in there practicing the tune away and of course he lost all track of time, and of course the father who wanted this field ploughed, came upstairs, reefed him out of the bedroom, clattered him around, he said he got a right clatter around the ears, and he said "Out!". You know, he was terrified that he would 'go to the bad’ by getting obsessed with music, and that he had to say no, no this is not something we do in the middle of the day. So we have all of that still, it’s not active any more, for sure. Then the other problem is "The Wild Atlantic Way Syndrome" so called, which is what I call it, "The Wild Atlantic Way Syndrome", it’s a complete disconnect. So on the one hand we’re sent out there to be cultural - to represent Irish culture on public occasions, state occasions, and then, even worse, to service the tourism industry. Now that is indentured slavery, as far as I’m concerned, and it breaks my heart to see young musicians - and not so young musicians - growing old in public houses playing for those kind of gigs. But there are some glimmers of light. People are taking it back, taking the power back from the public houses I suppose, some of them are terrible, some of them are not so bad, so there’s something very creative and challenging there to be done around gigs, and how they’re presented, and how the music is actually given, even to visitors given that there are a lot of well-disposed visitors coming to the country. And I do know one musician, Brenda Castles, I don’t know if any of you know her, but she does a very bespoke kind of - her own way of presenting the music in Dublin, basically to tourists, and a lot of them are Americans. But she kind-of says look, this is kind of what we’re told you’d like, we don’t believe this is what you’d like, we think this is what you’d like, and she takes it from there, and she has constructed a whole little tour around - both in terms of repertoire and where they go, on what actually we would like to show you and we would like you to hear. And she said… she omits from that every single bowdlerised, clichéd, you know "four on the floor" type stuff from that. And they like it, and appreciate it, and she puts in an enormous amount of work into it, so I think it’s going to take that - I'm sorry I’m wandering off far and wide, but they - that would be my one advice, would be staying creative, hang on to it, in terms of - like very few traditional musicians are going to have in one way the good luck, and in a bad way, the challenge of going into the rooms with the suits in the music industry. But there is a site out there, many of you know it, Creative Commons, which will … has templated licences up on the site, which will give you control over your own material, where it’s played, how it’s played. The digital world is where it’s at, for anybody under 40 I guess, who don’t listen to live radio, don’t get their - get all of their information from where they like, when they like, on devices and so on, so that’s where traditional musicians should be. And so think podcasts, think embedded music, think collaboration and that’s it. That’s about it.

Joanne: Thank you Nuala, that was great. Actually, just picking up on something you said about the role of the female as the lead singer, if you think about a lot of the bands that have made it commercially successful in Irish traditional music, often the role of lead singer was filled by a woman and it was actually rare to see a woman instrumentalist female as a lead, just something to think about. Muireann, I’m going to move on to you ...

Muireann: Speaking of which ... funny you should say that! ...

Joanne: So yeah, Muireann is an award-winning traditional singer, the lead singer with Danú and also a flute-player.

Muireann: Thank you! I’m going to stay here because I’m really scared. So, I already have a plan of what I’m going to say, but I thought I’d tell you a little bit about my own scéal, and a couple of points of maybe what I’ve learnt along the way that I feel might help you. What’s so encouraging and important to me about FairPlé is that we’re all here to support each other. And I know Pauline you said you felt removed from a community earlier – I do feel part of a community and it’s a very important community to me, and I think it’s important that we sit and have these conversations, and today has been a great benefit to me and I hope other people have gotten something from it as well.

So I’ll just go from the start, first, how I got into professional ... oh yeah there’s the other thing, what is professional? I don’t see an ‘idirdhealú’ or a distinctiveness, distinction between people who are making a living, and people who aren’t making a living, or maybe playing the odd session but they have a "proper" job. We’re all in this together in various shapes and forms, and you might play for money for some part of your life, and not for another part of your life. But there are a lot of pains and issues that affect us all as musicians.

So, I grew up playing music with my Dad, he plays the fiddle. I didn’t grow up through the competition scene at all, it’s ... I have no clue of that world. I went to the pub, to Bricks, every Friday with my Dad, and I played with him and his friends from the age of about 9 - I’m not sure you’re allowed to do that anymore! And I used to be told when to play and when to shut up and it was a really good training for me. It was with all men, for the most part, and they were very good and decent to me and kind and I have great memories of those times. And then I went to Dublin, found a couple of sessions in Dublin - there’s the lady down there I used to play with, Bianca. Well, Bianca was in minority, it was mostly fellas again, but it was, again, very welcoming, very enjoyable. Went to U.L. after that and did the Masters, because I just did not know what to do with myself. I went to Art College, which is even worse than doing music in college in terms of having a job at the end of it. So I went U.L. to try and get my head together and I did a Masters in music performance and kind of concentrated on my flute playing, and practicing – because everything to me before that had been about just playing in sessions, to actually spend hours trying to hone a craft was kind of new to me, and because I hadn’t been practicing for competitions, it kind of gave me a bit of discipline and helped me get my head straight. What ultimately came out of that year was I made a CD as part of the Masters, you had to come up with some kind of a product, like a tutor book, or whatever, a DVD, and I made a CD. So the lads in Danú, who are a traditional music group, for those of you who mightn’t know who they are, they’re quite a big group, and I was ... I would have been a fan of them and they heard my CD, and their singer, Ciarán Ó Gealbháin was leaving, to go back to college, and they were looking for a singer. So they phoned me up and asked me would I join the band, and I felt like I had won the Lotto. Like I didn’t even know what it meant, That I was signing up for, but I was like – YES absolutely, and I was so excited and 13 years I spent with them touring all over the world.

At the height of our touring it was about 200 gigs a year. It was gruelling, I’ve seen it all, I’ve slept on bathroom floors, I’ve slept in 5-star hotels. I have seen it all, and there’s so much here I can’t even tell you what I’ve seen, but you know what I mean - I’ve seen it. And I thought I was great, you know, I was the singer, and that was great, not that I thought I was great, but I was very happy in my position there as the singer, and I felt so protected because these guys already had a reputation. And they were older than me, there was six men and myself and I never had to worry about being good enough and stuff like that, because I thought well the guys are really good anyway. You know sometimes I’d be so nervous about playing with them that I would just like mime and hope I was getting away with it. But that all went to hell in a handbasket when Tom Doorley left the band, and instead of getting a new flute player, they said, "Ah sure you can just play the flute." and I was like, "Oh God ... " So I had to really dig deep and try and find some confidence to fill those big boots of Tom's, and play, and sing, and it was intense and it was an experience and an education and all that.

And I did feel like one of the guys until I decided maybe I should have a baby. And that’s when things went really wrong ... you know, I was really considerate and planned my pregnancies around touring which I thought was great, I got away with that, I was lucky enough. But my first baby was premature, so we were 6 weeks in hospital with her after she was born, and there is no maternity leave, you know, for the likes of us, and the gigs are booked, and you just have to do them. So two weeks after I took Sadhbh out of hospital, she was strapped to my chest on the main stage of the Cambridge Folk Festival and that was what it was, you know, and I kind of thought that I was going to show everyone that you can have it all, and you can do it all. And so I just doggedly continued to try and be a mom and tour with this very busy band. And I brought Sadhbh on tour with me, sometimes, and that was hell. Babies don’t understand jetlag, that it’s time to go to sleep now, even though it might be three o’clock in the afternoon in Ireland but it’s bed-time, they don’t get that. So I lost my voice on one of those tours and I couldn’t sing at all from lack of sleep. And then I decided right, well, I'll leave the kids at home so. So I left Sadhbh at home, and that was very hard as well, as any mom will know, especially when they’re babies. And then I said, "Sure, this is going so well I’ll have another baby.!" So then I had another baby and there’s a kind of a year there, where, to be honest with you, where I don’t even really remember. Because Danú started to do really well around the same time. They got this new American agent, the gigs got bigger, and the gigs got so big that you weren’t allowed to gig within 2 hours or 3 hours of the last gig, or even within the same state, so it was gig-fly, gig-fly, gig-fly to get to where you needed to go. So I left Laoise - she was only 3 months old, and I left her behind, and I went on the road. And that was, like, one of my biggest regrets. I should have called a halt to it then and there, but I was still like ... I mean, I don’t know why women do this to each other, like, we need to tell everyone how hard it is. It’s not easy! You can’t really have it all, you got to ... like something’s going to give. And what gave for me, in a way, was my health, and I just ... I was just in a fog. And at one point I was sitting on the couch thinking I was going on tour the next day, and the phone rang, and it was Benny from Danú, and he said "Ah well, girl, we’re at Gate A22, where are you?" and I was like "I’m at home, where are you?" and he was like "I’m in New York!". So I got my dates mixed up and they were gone on tour, and I had totally messed up everything - like, it was just a complete disaster. So anyway. Ultimately what happened was - I needed time out, I couldn’t keep it all going, and the time out was not really available to me. They needed to keep going, so I had to stop. And it was pretty devastating because I had worked really, really hard and it was starting to actually go right, but I couldn’t do it to my family, and I realised that having it all means such, ultimately sacrifice, for your health: for your mental health, for your family, for so many things. And even for your music, you know, you’re not playing great music, you’re just trying to keep going, you’re just trying to keep breathing. So yeah, it all kind of had to stop. And I realised that all my life I’d been playing with my Dad, or you know surrounded by men in Dublin, surrounded by men in Danú, and suddenly there I was on my own and I had no confidence, I didn’t think I could do anything, I thought I had no job, I didn’t know how I was going to feed the kids, I mean Billy has work, but you know it’s not enough, we had to both work. And Conor Byrne said to me "I hope you’re going to keep singing?", and I remember saying to Conor, "I genuinely don’t know what I’m going to do." And then I got a phone call from Maggie Breathnach from Red Shoe Productions and she said "I hear you’ve retired" and I said ‘Oh, ok, yeah I don’t know what I am, that could be a term for it’. And she said "Well, we need someone to present this programme", or whatever. And I had done little bits of telly and enjoyed it, because it involved talking to musicians and meeting musicians and like I said, I love so much being a part of this community and getting to know other musicians, and chatting to them. So Maggie kind-of gave me a little boost, and I did that gig. And then I kind of started doing little bits and pieces here and there, and realising that I had music in me that still needed to be made and that it was a part of me, and that I couldn’t not make it.

So after a year, a really grim year of feeling empty and being very hugely supported by a lot of these women here today, which is one of the reasons that I am so proud to be a part of FairPlé, is – so I made a new CD and I started touring. I can’t believe it like, that I’m working as a musician, I don’t even know how I am, but I am. And I’m making albums and I’m getting gigs and my confidence is much higher now than it was, it’s not fully there, but I don’t think it should be fully there because we all have to be very critical of ourselves. But one of the things that really helped me was other people, other people’s pep talks. So one of the things I will say is that it’s very important that we all encourage and support each other, and be there for each other. And if somebody plays something nicely or sings something, just bloody tell them you know! That you love what they’re doing, because that just means the absolute world. I don’t – like as Cormac was saying to me earlier - yeah it’s quite a presumption to think I want to make money. I want to make a living as a professional Irish musician. I don’t really think there’s hardly anyone doing that. So you have to diversify if you’re in this business, which ... I hate that word but, like, I do whatever. I do Skype lessons, I play for the "Wild Atlantic Way" pub sessions that break me sometimes, but I do it if I need to. Other times I’m up on big stages, I do telly, I do radio, I’ll do whatever you want me to do, as long as it’s to do with music within reason. I enjoy it and I’m my own boss, I’m not going to be a millionaire, but I’m happy. Finally I’m nearly 40 and it took this long to figure out my way through all this.

So here are a few points. Diversify. Like Éamon was saying: upskill as much as you can. And like that doesn’t mean learn tech, but for me it became learn how to be a teacher, learn to verbalise what you’re doing as a singer so you can explain it to other people, learn how to talk in front of a camera, or learn how to interview people. That’s what I had to do. Yeah. Boost other people’s confidence when you feel it need a boost if they deserve it. Don’t be afraid to throw a compliment at someone, as an Irish society we’re not great at raising people up, and I really hope we learn to do that more.

I got an agent, it took a while to make that step, my God having a buffer has been hugely beneficial. Someone who can ... nobody wants to be the bitch, and I’m really, really bad at talking about money and stuff anyway, absolutely hate it, so I was just doing things for nothing all the time. And sometimes I still will if I feel it's someone I want to support or something I want. But you do need someone to look at that side of things for you if you can, unless you’re hard as nails yourself and I’m just not. So I got an agent and that has been really, really helpful. And get an agent that looks out for you, rather than always looking out for the promoter. Because the agent I had in the States cared more about his venues, than his act - and that meant, you know, he could lose the act but he still had the venue that he could secure for other acts, and that was kind of tricky.

Being front-and-centre, women, if you’re front and centre in the photographs, doesn’t necessarily mean you’re front and centre musically, or in terms of equality. And I think a lot of people have said to me "I don’t know why you’re involved with FairPlé sure you used to swan out there with Danú and everyone was looking at you!". That’s not always a great thing, I didn’t always want them to be looking at me! I would have much preferred they were looking at Donnacha, I was always looking at Donnacha as well, but there’s a lot of elements to being this lead singer that actually I hated. And I was part of the problem, like Karan has said herself: I was just so flattered to be asked, and to have a gig. I took it and I did it, and I couldn’t believe that I was in that band, and I was so lucky. And it was great, but you know, I’ve developed a lot as a musician since then, I think. Since leaving the band I’ve had to be creative musically, I’ve had to explore other genres - that actually I’ve really enjoyed - that I was afraid to do. It’s a lot about feeling the fear and doing it anyway, and caring a little less about what people think of you.

And don’t sign anything without a lawyer present, that’s all. I did that three times, it was a bad idea. Thank you!

Joanne: Thank you. Just finally there we have Ciara O’Leary Fitzpatrick, she is a concertina player from Cork and she is currently head of Digital Marketing at Cork Opera House. So please welcome Ciara.

Ciara: Transcript not available

Joanne: Thanks, Ciara for that very empowering speech, that was really empowering.

Transcribed by Niamh Parsons.

Proofreading and editing by Úna Ní Fhlannagáin.