PANEL 2: Playing with Power - Sexual Harassment & Workplace Policy

Saturday, September 8th 2018, 2pm - 3.15pm, Liberty Hall, Dublin

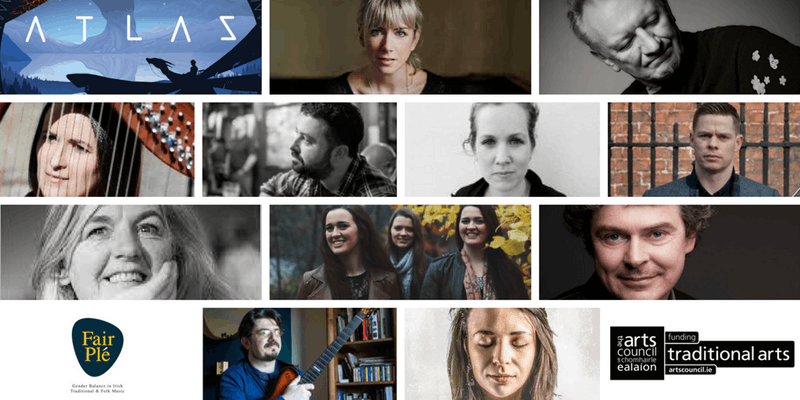

Panellists: Ellen O’Malley Dunlop, Paul Henry & Pauline Scanlon

Chair: Úna Monaghan

This panel discussion addressed the issue of sexual harassment in the arts and Irish music, with a focus on the self-employed status of musicians. Our participants explored the rights and responsibilities of employers, promoters, agents, sound engineers, teachers, producers and performers of all genders, and provided unique insight into their own experiences within their respective disciplines.

Chair:

Úna Monaghan is an Irish harper, composer, sound engineer and the Rosamund Harding Research Fellow in Music at Newnham College, University of Cambridge.

Panellists:

Paul Henry is a Trade Union official, studied Law in DIT Aungier Street and then trained as a barrister in Honourable Kings Inns and became a qualified barrister in October 2016. He heads up the Workers Rights Centre in SIPTU. This department represents individual members in their workplaces and at third party hearings, such as at the Labour court. He also studied sound engineering and worked in theatres and venues in Ireland.

Pauline Scanlon is folk singer from West Kerry who has been performing internationally for 20 years. A curious collaborator, she has performed and recorded with many of Ireland’s best-known artists. She is a founding member of FairPlé.

Ellen O’Malley Dunlop is chairperson of The National Women’s Council of Ireland. Ellen is a committed feminist, and for 10 years led the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre and raised awareness of the prevalence of sexual violence in Ireland, lobbying tirelessly for victims rights and legislative change. She is a qualified primary school teacher and psychotherapist, became the first woman chair of the Irish Council for Psychotherapy, and lobbied Government on issues of suicide, marital breakdown and children’s rights.

TRANSCRIPT

Úna: My name is Úna Monaghan, I’m a harp player, I’m a composer, I work in academic research on Irish traditional music and experimentalism and I’m also a live sound engineer and I’m going to chair the "Playing with Power – Sexual Harassment Workplace Policy" panel discussion today. And we have three wonderful experts again, with a really diverse range of experiences.

Just before we start I want to draw your attention to the wonderful work at the back of the room. This is Blanche Ellis who is live drawing the work today, and if you have things you want Blanche to include, let her know. We’re really pleased to have this visual representation of all the talks that are going to happen today so that we can share them later. And I think with all of these kinds of nuanced debates it’s really important to try and have lots of ways of representing them so that it comes from different voices, but also different ways of portraying these points - not just speech, not just text, but also visual and through the arts.

So, just to give you an idea, we’re going to have an hour and fifteen minutes. I’m chairing the panel but I’m also going to speak for ten minutes as well – I’ll speak for 10 minutes, then we’re going to have Pauline, then Paul, then Ellen and then we’ll see if we have any points arising from what we’ve heard to discuss, and if we do, we’ll have that discussion, and then after that there’ll be questions from the floor and we would love to hear everyone’s input and feedback.

So my starting point for this – in this case came from a place, I guess, of creative work. I’d been working in the industry for ten years / fifteen years myself and had experienced all of these little subtle things in terms of inequality. And one in particular really got me to the point where I was furious and I thought, "Actually, I don’t think there’s anything I can practically do about this", so I decided that I would write a piece of music about it and that every time I performed that piece of music that it would be some way of just letting out the frustration that I was feeling. So I went ... I started to write that and then I thought, "Well, what if it isn’t just me, what if I don’t use this as just my voice, I don’t have to be just one voice complaining, I could maybe include the voices of many other people because that will give weight to the argument." So I asked for submissions of stories online and I got quite a lot of those stories, it seemed to me that they were coming out in different themes, these were from very, very subtle things that you could easily explain away if you heard them, but they ranged right up to a lot more serious things, sexual assault and harassment at the very… more serious end of that scale. So I then felt as though some people really did feel they like they could not share these very publicly – one of the stories I got in was "I wish I could tell you what happened but I can’t" and I thought that was really powerful as well. So as FairPlé then went ahead, we’ve developed this into a more robust research project.

So I’m going to make 6 points today and then maybe have some suggestions for what we might do to move forward and I’ll try and illustrate those along the way with some stories.

So the first thing I want to say today is to address the fact that some people don’t actually realise that this is real, both the topic of sexual harassment and the fact that gender affects people’s experience of playing or experience in traditional music. Sexual assault and harassment does happen in our music industry, and yes, in the corner of our industry that is traditional and folk music.

So I’ll just read two of the stories that have come in on that topic. “A well respected, well established traditional musician sat beside me at a session and put a hand on my leg and told me 'You’re looking well.' I asked him to take his hand from my leg and he mocked me. The same man, at another festival, snapped my bra in a session. In another instance, a local musician in a town I was visiting pulled me down into his lap as I walked passed and asked me to play a tune."

Second story and I quote “I met my all-time fiddle hero at 16 and I was in complete awe. I managed to get sitting next to him at a session that night, and I was so excited to get to hear him play, and play with him. As the night went on he continually felt my thigh in full view of the entire bar. I was 16, I was gutted, never meet your heroes”. So there are many, many more examples of those that are coming in through the research project, those are just two.

The second point I want to make is about the "Playing with Power" part of this panel. Sexual harassment and abuse are thankfully in the minority of responses that have been sent in, but there is a power imbalance, there is a culture that favours men and relationships between men and this music. I’m thinking of an article I read recently by writer Andrea Dominick on the wider music industry. She says respondents described working in a boy’s club where deals are sealed over late-night drinks and backstage parties. They told stories of powerful men who took advantage of their positions and explained the risks inherent in speaking out against them. They detailed an industry beset by financial pressure and fierce competition, increasingly reliant on a freelance workforce, vulnerable to gaps in labour protections and that is the case in our industry. The music misconduct problem does not stem from any one of these factors alone, it is a perfect storm that clears a path for sexual abuse to continue unabated. Blocking that path will require reckoning with the very nature of music, and the industry and cultures that surround it. So sometimes these attitudes and behaviours mean women simply won’t get the work. This is unrelated to their ability or willingness to work. And I think that imbalance in and of itself is one of the things we’re told is not a problem but when that imbalance affects self-determination, that is problematic.

The third point I want to make is about the fear of making a scene or upsetting the status quo, and I’m thinking of the unwanted sexualised touching of Ariana Grande by Bishop Charles Ellis at the funeral of Aretha Franklin just recently. I’m quoting from an article by Clementine Ford in the Sydney Morning Herald: "In that moment, every single lesson Grande has learnt regarding 'polite femininity' would have been informing her response, chief of which is this: don’t embarrass men. ... I can well imagine how humiliated Grande felt as Bishop Ellis told her with words how well she performed, while telling her through actions how little that really mattered." There is a sense of how you’re expected to act. And I want men to know, not really to be so weird out when women don’t act that way, and we’ve had online instances of defensive or angry reactions when called out, or when women ask to be treated fairly they get "put in their place".

So I’ll just give another couple of examples from the questionnaire. “When I joined the band, their manager took me aside and told me that I wasn’t to get above myself, this was our first gig, and that they were a great band before ever a woman came along, to remember that”. The second one, just about that humiliation and the defensive response, I’m just quoting from another story “Two older male musicians came in and sat in the seats ….”– and this is also to show that this is about …it’s not just for professional musicians, this happens throughout the traditional music community… “Two older male musicians came in and sat in the seats of where normally the two female lead session musicians would sit, me and a friend. We, the lead musicians, said they would be most welcome to join but would they mind relinquishing those seats so that we could do our job of leading the gig. We were extremely polite. Disgruntled they moved, and continued to lead all of the sets without waiting to let others start. We, the lead musicians, made sure to invite the other guest musicians to start a set so that everyone felt included. Eventually I started a set once I felt everyone had a chance to play and could relax into the rest of the evening. As I lifted the fiddle, one of the men turned around and said ‘Good girl, you know a set of tunes is when you play a tune and then when you put another tune after it that makes a set, right off you go, good girl’… I was 32 at the time.”. (This isn’t me, this is somebody else’s story) “I know this is bordering on the ridiculous but it is just an example of how you constantly have to negotiate your space as a professional musician so as not to bruise the ego of others in a male-dominated space, it wouldn’t have happened if we were both male lead musicians.” So can you be ok with women being equal or even better at something, can you not feel threatened by that, and don’t feel like your response needs to be coming back out on top.

The fourth point is about professionalism and we touched on this in the last panel. This music has come from a social music, and we have to realise the professional boundaries and that can be harder if it’s coming from a place that was not historically a professional space. We have to see this as not being about being uptight or demanding, and because there may be other reasons for that, reasons that are about safety for some people, reasons that are about trying to avoid consistently having to counteract forces, that in the absence of standards, just pan out into inequality.

The fifth point – to speak to those who think this campaign is merely professional, there are many instances of these stories coming to me in non-professional contexts, in sessions, in traditional music lessons, there’s a power dynamic. This talk here is by no means a proper analysis of the stories that have come in, I’m going to write them up and present them hopefully at the symposium in February. But just to give you an idea of the fact that it’s not just always about the professional sphere, whenever FairPlé started I had some really interesting conversations with high profile musicians who …. The ones that didn’t really, weren’t completely convinced by it who phoned to say "What is this? what’s going on?" And I love those conversations, some of them took ages, like this particular one I’m thinking of took an hour and a half of arguing hard, like rang me to discuss it, saying they were struggling to understand and agree, and we had a really long conversation in which I argued, and at one point the musician said that "When a woman arrives in a session I expect a certain level of competence, if she’s remarkably good, I’m surprised" – like listen to that, listen to how you literally write off a whole half of the population. Now whether that’s true or not, it’s unacceptable, and you can speak about probabilities and 'on average', or probabilities that may be the case, yes, you can look at it from that point of view, but if we look at it from the other point of view that as a woman walking into a session, before you even take out your case, that there’s this judgement made, that’s a pretty grim reality, you’ve a mountain to climb there before you’ve done anything.

So the last point before some possible considerations about it is to try to be actively aware. I’ve noticed in this work when the stories are coming in that my own stories have gradually trickled through to me, they haven’t all appeared at once. We’ve been in this work for quite a while, and in this society for even longer, and it’s astounding how much of this is internalised, normalised, even part of the infrastructure we use to get work, it’s now built in to our professional skill to counteract and to get round this. I’ve learnt my craft as a sound engineer in this context. I know how to arrive at a venue and make sure a team of five tech guys will have some respect for me, but I have to be awake to that, and sometimes fight for it. I can name the ways in which I’ve adopted this or to fill gaps in demand or to make myself unique in a competitive industry. And secondly I’ve had conversations with people that start out as "I've never experienced that" and after the conversation has gone on, they’ve noticed a different way of looking at some behaviours that make them think "You have to try to notice this, actually." It’s not the same thing as saying it’s not a problem though, if we don’t make the effort to examine it, it won’t change, and these things are often involved musicians that we love and respect, we’re not programmed to want to interrupt that person and their way of operating.

So I’m just going to finish with some possible considerations that might help. We need allies everywhere in society, this is a societal issue that bleeds into our music. We need allies to work with us, not just when we’re at work, but to call out stereotyping of women, not to refer to the wife as a caricature, not to settle for banter in WhatsApp groups, and we need you to ‘kill the craic’ just a tiny bit in order to support those of us who have to ‘kill the craic’ just to get paid. We need men who are working in the music industry to be aware of it. I’ve had testimonies in that have said "and the worst thing was that it was happening under the noses of my bandmates." And in some cases when they told the bandmates, they were horrified but that was also after telling them as it was occurring. The bandmates were shown that when they had listened, you know they were then horrified. So believe women when we say we’re uncomfortable, or that something has happened. And to give an example of that: "I co-lead…." (I’m quoting from someone’s story) "I co-lead a band with a male colleague. The majority of the band are male musicians, we’ve around 25% female musicians. I have, on many occasions, directed the band in rehearsals, and at various times during this direction, some of the men will look to my male colleague and I and blatantly ask him in front of me and the rest of the band what he wants the band to do, as if I’ve not spoken at all, or will for assurance that what I’ve just asked is what he wants, or screw their faces up, making inference that why she thinks she runs the band. One of the most annoying things about this is I had to take my co-director away and tell him it was happening. He didn’t notice it, the women in the band noticed but none of the men. My confidence slowly deteriorated throughout that time." If you see someone sticking their neck out, pointing something out, or killing the craic, decide carefully whether you want to turn a blind eye, which is often excusable since the behaviour is not usually straight forwardly negative, and it’s usually an easier thing to do or do you want to make the effort and be seen, and support those people. There’s no such thing as innocent bystanding. Try to make an environment where if someone were to challenge these subtle behaviours, that they conceivably could. What haven’t we heard? There’s an opportunity to hear new music in this if we’re able to create a culture that is more diverse. At the minute the music we hear favours the voice that has stamina, confidence and can last the shit. Is that a particular type of music, do people conform to that to survive and the men in this story certainly think so. “One of the reasons given to me for being kicked out of my first folk band was ‘You’re a girl so you don’t really fit the feel of the music’ ”. So there was a perception of what the music was and whether she fitted that. And the second story, “Many times I was asked as a representative of the female sex, why women couldn’t play with balls, what was the story with that? 'Not you, though,' they said, 'You play like a man.' In my ignorance I took it as a compliment because they never complimented me so it was better than nothing." So there may be a sense here that there’s music to be heard.

I’ll just finish, I can sum up all of these topics, all of the different stories that are coming in, they’re all a really broad range of things that are happening, but they’re always of a rolling confidence intentionally or unwittingly. Can we actively build up confidence rather than tearing it down? Would this be a more comfortable industry for everyone then? And can we acknowledge rather than giving advice – I think if we just start by simply acknowledging that this is happening and that it is real. If that is just the place that we start with from today it would be a real help. Thanks.

I’d like to welcome Paul Henry who I hope will be able to maybe speak to us a bit about the workplace policy aspect of this. Paul Henry is a Trade Union Official, head of the Workers Rights Centre in SIPTU, a barrister, and a sound engineer. Please welcome Paul Henry.

Paul: Pauline asked me was I nervous before I started and I said no, but I am now after hearing Pauline. I mean that was really personal, it was very moving, it was very moving. I come from a working background, a working-class background. My dad died when I was 10 years of age, he was 42, and my mother became the breadwinner and she worked for pittance in hotels. I watched beg men for work, I really did. I left school at an early age, I worked in every job imaginable, and in my 20s I done a sound engineering course in Temple Bar, and bought a rig, and myself and a friend spent long days and nights travelling up and down the country doing sound in absolutely awful venues. I became a qualified Barrister in 2016 and I’m currently now, as Úna said, head of the Workers Rights Centre in SIPTU. That’s a department that was set up by the Union representing individual members in the workplace at the Adjudication Service at the Labour Court. I haven’t managed to get the gender balance in the department equal just yet. At the moment we’ve 20 women and 10 men. But when I was asked to speak here on Sexual Harassment, I was worried to say the least. One of the briefs that was sent to me from Karan in the first place, she said make it personal, practical or your political experience, and I thought 'Well, I can do practical, I can’t do personal and I'm definitely not doing political.' Well, whatever! Through research I found a piece of American research that resonated with my experience of the Workers Rights centre. The music industry, like the rest of the economy has seen a rapid growth in the last number of years in contract workers, and freelancers, and the research found that even fulltime employees may be reluctant to come forward with claims, and it’s not unique to the music industry. According to the study, at least one in four women had experienced workplace sexual harassment but only 30% of those people were likely to talk to a supervisor, a manager or a union representative, and even fewer, between 6 and 13% ever made a formal complaint. And I thought, that’s my personal experience. Very few members of our Union make formal complaints of sexual harassment, but when they do come to the Workers Rights Centre we treat them professionally, we listen to them with empathy and we give them the necessary advice and representation, and that’s my practical experience that I’ll return to. So at present in relation to the legal grounds, there’s approximately 35 pieces of employment law legislation in this jurisdiction. And SIPTU would represent most of their members, and most of those types of those different pieces of legislation. They go from the ‘Part-Time Workers Act’, to the ‘Protected Disclosures Act’ (more commonly known as the ‘Whistleblower’s Act’), and ‘Unfair Dismissals’. And the application of each of these pieces of these legalisations depends on the employment relationship, and the term ‘employee’ and ‘worker’ is interchangeable and it depends on the breach. I intended to focus on the ‘Employment Equality Act’, because that’s where sexual harassment is dealt with in the workplace.

One other thing I was asked to talk about is, 'What’s the advantages of joining the Union?' So the Musician’s Union of Ireland is an affiliate. It represents musicians of every genre, along with music teachers, singers, freelance or directly employed, and they tackle exploitation, and they’ve a successful track record of insuring that people receive their entitlements, and as an affiliate of SIPTU they benefit from the expertise and experience of the largest trade union in the pursuit of fairness and workers’ justice in society.

So practically what does that mean? So in relation to your own industry, how do you make a contract when you get a gig, and make sure you get paid. Well you could send a text message to the owner, or the person acting as his agent who booked you, confirming the agreement to play for let’s say 500 euros in Liberty Hall from 9 through 11 and the payment is due when the performance ends. And if they don’t pay up you could maybe pursue them through the small claims court.

So we give advice in bullying and harassment in the workplace, and the advice we always have to say to people is "You know, you need to tell somebody about the bullying." We help them identify the bullying behaviours: is it verbal, is it physical, is it psychological or is it cyber-bullying? We then will advise on what steps to take and we’d always tell them to keep a diary. Sexual harassment, we’d also say tell somebody, be informed, know what the policies are, know how to access the policies. Sometimes with sexual harassment, they maybe able to… the person being sexually harassed may be able to deal with the issue themselves, but we always tell them to keep an accurate record. We offer trade union representation to people in bullying and harassment in third parties, and through formal and informal procedures or in mediation. Another thing the union would be good at and again with your own industry, you need to pin down the person who can be responsible for the actions of the sexual harasser, or it would be more appropriate to call them the alleged sexual harasser in the beginning, you see you need to establish a paper trail, think for instance the Electric Picnic event or an event that’s just taken place, the event organiser submitted a method statement to the local authority to do that, so a trade union like SIPTU could log local authorities etc. cover and make sure everybody is covered by employment law legislation. In turn that event organiser should insist that all persons on the site are compliant, thus creating an avenue to deal with the complaints. In relation to sexual harassment, the ‘Equality Act’ - Pauline cited from the ‘Equality Act’, and the Act refers to the employee as a victim, so where the victim is sexually harassed either at the place of work or where he or she is employed or otherwise in the course of her employment, if the harassment, the sexual harassment is by a client, a customer, or other business contact, the victim’s employer – the employer is expected, and ought to have taken reasonable steps to prevent the harassment or sexual harassment.

So from a practical viewpoint I just like to share a story of one… of someone I represented. Martha was a Polish woman who worked in a well-known restaurant in Dundrum. Her manager, he was making jokes that made her feel uncomfortable. He then asked Martha out for a date, and he also began to touch her inappropriately - clearly sexual harassment. Martha was a confident person and brought the situation to the attention of her employer. Her employer refused the right to representation so I supported Martha and got the employer to investigate her complaint. And he found that, he said, her grievance was substantiated. So in other words what that meant was she was sexually harassed. They moved the manager to another restaurant on the other side of the city for a while. The manager began to be rostered back in the restaurant at times Martha was being left alone, opening and closing the restaurant. This was affecting Martha’s health. She resigned. SIPTU took a case of constructive dismissal to the Employment Appeals Tribunal and won Martha €20,000. This is the type of practical support SIPTU offer. We, in SIPTU give our members representation. We weren’t allowed to represent Martha in her workplace, however we supported and represented her in the third party and that case was the Employment Appeals Tribunal. We secured – we negotiated €15,000 extra for Martha for the sexual harassment.

I spoke earlier that I briefly worked in the music business and in reflection, looking back, I only came across one woman who was a sound engineer. Sue was her name, extremely competent sound engineer in all disciplines, live sound, theatre sound and in studio, that was over 30 years ago, and it strikes me following FairPlé on Twitter, the numbers may have gone up, but the challenges are the same. I couldn’t stand up here today without mentioning the trojan work and the awareness of the #MeToo campaign, and what all the other campaigns have achieved but I can’t help but wonder, does a factory worker, or somebody that works in a retail store, or somebody that works in the financial services sector, see a musician standing on the stage in a venue, in any genre of music, including traditional and folk music, as an employee, as a worker, or self-employed, and entitled to the same respect and dignity in work that they are entitled in the workplace. I came across a catchy tagline on worknotplay.co.uk where it said "This is not a hobby, it’s a profession" and maybe all musicians should say to their audience, or at least have a sticker prominently displayed at their gigs.

And that’s all I have to say and I hope that what I’ve said will provoke some discussion and look forward to your questions, and we’ve prepared a flyer about what SIPTU can do, what the trade union can do. I’ve left them on the table and you can take one, I hope they can be of some assistance to you.

Úna: Thank you Paul for that talk from the Union perspective and if you have any specific questions for Paul afterwards that would be great.

I’d like to introduce Ellen O’Malley Dunlop, she is chairperson of the National Women’s Council of Ireland, having led the Dublin Rape Crisis centre for ten years. She’s a qualified primary school teacher and a psychotherapist, a real breadth of experience on this topic. Please welcome Ellen O’Malley Dunlop.

Ellen: Thanks very much, and I’m really privileged to be asked to speak today and I think what you’re doing is fantastic, and listening to the stories, your story Pauline, and the stories that you have been telling us about the people who’ve been emailing you, I can’t help but feel how important it is that you are organising yourselves and you’re going to have your codes of practice and your policies and procedures because reclaiming our boundaries and our space is so important because that’s what rape and sexual assault is about, it’s about breaking of boundaries and I was reminded of the SAVI report, the Sexual Abuse and Violence in Ireland when I was in the Rape Crisis centre, and like if you’re in any doubt as to what’s been happening in this country, SAVI was the most extensive piece of research ever done in this country on attitudes and beliefs to sexual violence. And it told us that rape, which is the second most serious crime on our statute books, over the lifetime of Irish women, two hundred – if we take our population as 2 million women and 2 million men, 200,000 Irish women over their lifetime are victims of rape and 60,000 men. I mean those figures are absolutely shocking. And it’s wonderful to see you standing up and as I say, organising I think it’s so good.

I’m the chairperson of the National Women’s Council of Ireland, and we’re the leading organisation campaigning for equality between women and men, and advocating for women’s rights. We’re a membership organisation and we represent 180 member organisations across the country. It seems that everywhere we look in Ireland there are decisions being made as to where influence is being exerted that we find that women are underrepresented in the arts, on the radio and the television screen, in defence forces, in sport, in our higher education institutions, in politics and in the boardroom. Women are underrepresented apart from your organisation, are underrepresented in decision-making in Irish society, and more often than not we know that women are underpaid compared to their male counterparts. As a feminist organisation, the National Council believes that feminism is about working to change society so that women, and men, have an equal say in decisions that affect their lives. And how do we do this? Well the presence and active participation of women in central decision-making arenas goes to the heart of feminism, and recognises that women must play an active part in decision-making processes in all areas of society. It’s also very important for young women to see women role representatives, as, somebody mentioned it I think earlier, that you cannot be what you cannot see. So quotas are very important in this whole area. At the macro level in women in politics, in ... somebody referred to 1918 which was when women first got the vote, but we only had one percent in the representatives in the Oireachtas at that time, we’ve seen improvements in recent years where the numbers in 2016, went from 15% in 2011 to 22% in 2016. However research conducted in TCD shows that there have been more men named John and Seán elected to the Dáil than there have been women. Women comprise just 21% of local and city councillors, and there are no quotas there, so it’s really important that we insist that that happens as well. We want to see action address this under-representation of women at all levels.

The government has committed to a review of women’s representation across all sectors in their Programme for Government and have committed in the National Strategy for Women and Girls 2017-2020 to an action plan to promote women to senior leadership roles. Quotas must be considered as part of any action plans to promote women to positions of influence and the decision-making spaces. Because quotas work, quotas are a blunt tool but they have real merit as a mechanism for accelerating the pace of change and increasing the numbers of women represented in a tiny manner. And we need more women, we need young women and a diversity of women in politics. The National Women’s Council was one of the leading organisations in the ‘Together for Yes’ campaign, and that campaign was led primarily by women of all ages. The campaign saw one of the highest voter turnouts in the history of the state, and a resounding 'Yes' for access to reproductive healthcare in Ireland. The result was an incredible win for women and showed what women are capable of and what women’s leadership looks like and it’s about collaboration.

However the pace of change is snail-like unless we have concrete actions and goals and quotas are one practical way that we know gives results. Higher education institutions in Ireland are another example of where women are under-represented in leadership roles. Trinity College Dublin is over 400 years old and they’ve never had a woman Provost. Research shows that 50% of lecturers in University are women and only 21% are professors. Third level institutions face funding cuts now if they fail to introduce mandatory gender quotas to increase the number of women in senior positions, and that’s because of continuous lobbying. And we need change to come quickly because we can’t afford to wait decades for equality because we know that diversity in decision-making not only leads to better decisions and avoids 'groupthink', but it also has been shown to increase profits where businesses are concerned, we heard that earlier as well.

Equality and diversity in the music industry, in the theatre, in television, film industry, the boardroom, politics, in the arts, is a win-win for everybody. Ultimately the power base must shift from men to women so that all of society can benefit and quotas are a proven way to help achieve this. We need temporary quota systems across all of society until we reach that critical mass of sustainability. In her most recent novel ‘The Silencing of the Girls’, Booker prize winner Pat Barker goes back to ancient Greece and tells the story of the Iliad from the perspective of the women. It’s a sad tale, but we don’t have to go to ancient Greece to see the roots of how women were silenced in our own culture. The story of the Children of Lir is the story that is known to most of us growing up in 20th century Ireland, it’s a story of the silencing of the women and the children. It’s about, when you look at that story, it’s about the abuse of power, the abuse of women and the abuse of children. That’s one of our foundation myths. These underlying qualities have to be addressed at all levels of our society, both conscious and unconscious if we are to see more women progress in leadership roles. Sexism and rape culture have been with us for thousands of years. These stories do not carry good messages to our young children, and conversations about consent and quality need to start at a young age. Rape culture and sexism are ingrained in our society, and we know that from the robust research, and often we are unconscious of the messaging that is all around us.

However we are entering a new era in the 21st century. There is an awakening happening where we are becoming conscious of these issues and starting to address them. We can all play our part by calling out the little slights, the innuendos, by checking ourselves, as well as checking others. Recent events around the #MeToo movement have shown, yet again, what happens when there are such huge power imbalances in the workplace, across all industries, and where there is a total absence of feminist leadership. But #MeToo did not happen overnight, in fact the concept was initiated by Tarana Burke in 1997 when her daughter disclosed to her that she had been sexually assaulted, and she, as her mother, didn’t know how to respond to her. And ten years later in 2007 she founded an organisation called #MeToo to support victims of rape and sexual assault. But it was after the actress Alyssa Milano’s #MeToo tweet about Harvey Weinstein in October 2017 that the movement took off. So these things don’t happen overnight and I know what’s happening - FairPlé isn’t something that has happened overnight. What started as an exposé detailing numerous allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein soon became a countless avalanche of personal stories from women from around the world. A movement was born where women shared their stories of sexual harassment and assault across all industries and the #MeToo became a rallying against sexual assault and harassment. As feminists have been saying all along, sexual assault and harassment is about more than one man, this is about the culture which blames the victim and lets the perpetrator off the hook, and it seems that finally we are talking about it and beginning to address it, but we have a long way to go. Louisa Neelan in her book "Asking For It" has done a huge amount of good and opened up the necessary conversations here in Ireland with young and old people, particularly about consent, that we must continue to have these conversations in order to work towards challenging and changing the culture.

We have come so far since 1916 and especially in the last 40 years. In Ireland as late as the 1970s, women couldn’t buy contraceptives, couldn’t collect the Children’s Allowance in their own name, couldn’t sit on juries, couldn’t order a pint in a pub – but there is still a lot of work to do. National Women’s Council, and this is the big wish, National Women’s Council’s vision of Ireland is one where women are paid equally for the work we do, where care-work is shared equally, it’s a society where women are free from violence (I’m thinking big here) and fear, where girls can walk down the street, attend college, go to parties, without being sexually harassed, sing, be on a bus with a group and not expect to be harassed. It’s a future where women have full control over their reproductive health care and all their medical decisions. It is an Ireland that values survivor testimony, that has provided proper redress, compensation and justice for Magdalene survivors, to women who were incarcerated in Mother and Baby homes, and other institutions in Ireland. It is a future where survivors of symphysiotomy have been properly compensated and where women are recognised as experts throughout any pregnancy they have. We want Traveller Roma women and woman with disabilities in leadership positions, an end to Direct Provision and for the rights of trans women and men to be respected and realised. This Ireland sees our economy service our society, and ensures lone parents do not live in poverty. The feminist future is one with a progressive tax system, which funds world-class public services and a living wage for all. There are many opportunities to build a more inclusive society for women and the National Women’s council looks forward to working with you to achieve this. We need a new myth. We need to call on the triple goddess Brigid, not the saint now, the triple goddess, to garner the support, and we need the energies of the princes of the Tuatha De Dannan, but we need Brigid to sing Ireland into being.

Úna: Thanks Ellen for really broadening the discussion out to the wider society there which is, of course where all this starts.

I’m going to pick up on two things from the presentations, the first to Pauline and Paul. Paul gave a good run down of workplace and workplace policy in law, but the question as you said Pauline, comes back as musicians, as traditional musicians, what is our workplace, and how is that defined, and also the real question of..… it was clear from Paul how we report this and how we might report this, but I found myself thinking how do we deal with that question, that we may not be employed again. So how do we define our workplace, and how do we get around the fact that I would still have a fear that we would not be employed again if went down that route?

Pauline: I definitely don’t have the answer as to how I define my workplace, because my workplace is everywhere from the pub to you know, the tour bus. And it doesn’t end when you get off the stage, often when you’re on the road it’s 24 hours, you could be sharing a room, or ... it’s just … it’s pretty indefinable so I guess from my own experience where I feel that, because I think if we are to put structures and a respect and dignity policy together it’s going to be pretty hard to enforce it. I mean it’s up to us all who care about … actually as this movement progress I am less and less likely – I don’t really call it a community any more, because I think that everybody really in it is, kind of, very much a sole trader, and that word, kind of, to me, implies like we’re all there looking out for each other but I actually don’t feel really that that is the case. It’s not been my experience anyway. So I guess that for us to facilitate a way so that the next time, or if something like that happens to me again, that it’s really that the cultural, that the internal workspace of all of us, that that has changed somewhat and that I’m not viewed as being a pain in the ass for putting my hand up and going, you know, this terrible thing just happened to me or this person’s freaking me out, and you know, it doesn’t happen lots, but it happens, it happens regularly enough for it to be a problem, for me anyway, even to this day so. I don’t know if that answers your question.

Paul: Yeah I suppose as the law is at the moment, a case like this for a situation like this hasn’t been taken, so there’s no precedent in the law to deal with it as we speak here. I done a lot of research on it just to find out what… because I anticipated this question, so what we do in those situations is, we create the law, we create a precedent, we run with the case, we support a member through a very bad experience, to test the law, to find out what is the workplace, what is …. And then when you get a case and a win, and it gets published, that’s where it starts, that’s where the grounds, the foundation starts to move to answer the questions. Is on a bus part of your work place? Is it an extension of your workplace? Because I assure you that you can be fairly dismissed if you’re doing something on a bus when you’re going on a Christmas night out. So you can … that’s established in law now at the moment that’s it. So there’s the foundation, how do we ... It’s like how are …. What I was saying is, trying to pin down, right there’s the event organiser, it’s the person on site and it’s a paper trail to the person to do it, so it would mean taking a test case and getting the foundation there to try and do something and then it’s clearer, then the answers would be become clearer for it.

Úna: And Paul, just to clarify on that when you say a paper trail to the organiser, that kind of frightened me in your description about finding responsibility. Like to me in my head the responsibility with that person’s actions is immediately with that person right, and that’s true.

Paul: Oh yeah, of course yeah but somebody’s responsible for having that person on that site doing that thing so it’s a train, it’s trying to pin somebody down who’s responsible for having that person there. So each vendor on the site has employees on the site, that vendor is responsible for that employee’s actions.

Úna: Ellen do you have a response to that?

Ellen: Well I suppose the thing that I hear people being concerned about is that if I say something, you were saying Pauline, nobody would want to employ me again, and that’s a big thing when that stops victims reporting as well, and everybody saw what happened in Northern Ireland during that rape trial, while we have anonymity for victims in this jurisdiction but the exact same thing happens in our courtrooms. So it’s about changing attitudes and culture change and the way we do that is each and everyone of us has to take responsibility but we also need to do it collectively as well. And that’s why I think getting FairPlé and you know together, organising yourselves I think is really important. When I went into the Rape Crisis Centre first of all, I thought consent was a really important issue to have in the legislation, definitely, because we have no definition of consent in our legislation, and all the barristers and all of the legal eagles said, "Oh, we have enough case law" but we didn’t have enough, it didn’t make sense. So now, so we continue to lobby, and we got a definition of consent, but only together, so it’s together, it’s like that campaign Together for Yes, where we did it together and so organising ourselves, and addressing the need for that attitudinal and cultural change.

Úna: We’re three o’clock and we’ve 15 minutes, I’m going to ask for questions from the floor and if you don’t have any, we have some more up here. But do you have any questions?

Question 1: My name is Catherine, I work in the Arts Council and I’m a member of SIPTU but just in addition to the case law, and you know, creating the facts to an extent, I think there is another parallel step which is actually describing the workplace, you can put down… like let's make that a formal description, there’s the bus, there’s the tour, there’s the stage, you know, and from a legal point of view Irish law does support people against discrimination along 9 grounds, including gender, and … but the big issue is obviously enforcing that. But I think a pre-emptive step of actually describing the workplace is really important, and … oh yeah the other thing I was going to say about the legal side of it is – as regards discrimination and the work place, it actually doesn’t matter if it’s not officially in the work place, you know it can be a social setting afterwards, but if it involves your colleagues or pertains to work, then it’s something that should be pursued. But the question is it’s so hard to pursue it, so I think that one of the starting points is naming and describing the world, and the profession, and it actually came up in the earlier session as well, it’s like … what is this profession, actually beginning to describe that.

Úna: Thanks. There’s a question further behind too.

Question 2: One brief thing I’m going to say today but I find with this movement, everything seems to be really geared for people who work specifically professionally as musicians and in Irish traditional music, there is a huge variety of how people engage with this tradition and this genre and this beauty and like I personally…. I’m a scientist, I play music all the time, I’m not a professional musician, I can identify with everything everyone has said on the stage, many things happened to me that I’m really not happy about. I don’t have ... I can’t define the workplace, I don’t have someone to go to, to place any blame on, so like I just feel like where is the space for people who are not professionals and are obviously still, like I mean … I’ve come to the conclusion sort of recently having talking to my friends, my male friends and my female friends and the girls have been talking about for years, for many, many years, and the guys just don’t seem to know about it, because it doesn’t affect … it hasn’t happened to them specifically so they’re not looking out for it. And … but like, at least us, me and a lot of my friends, we feel that we don’t have any recourse because we’re not professional musicians, we’re scientists, teachers like if somebody in my work in the lab did something to me, I would have recourse, but I don’t have recourse when I go out on a Saturday night and somebody grabs my boobs, like I mean what am I supposed to do like? What are those people supposed to do like?

Úna: Yet to say also that I agree that a lot of the stories……yeah a lot of stories that have come in are based on professional experience and I think we see the result of these is that there are just fewer women, because it is not a comfortable place to work, if you’re not a professional musician, if you’re doing it socially, it’s not comfortable, I don’t find sessions comfortable. I don’t have an answer to your question. Does … ?

Paul: It’s a… There’s a criminality in it as well so there is that’s side of thing, a protection for people, those type of actions you’re describing are crimes under the Offences against the Person’s Act, so there is a criminal element to those actions as well as a workplace sexual harassment element to them.

First questioner: So sorry, can I say, could one just go and report to the Gardaí?

Paul: Most certainly yeah. It’s the ‘Offences against the Persons’ Act.

First questioner: Again there’s risk there in all of that.

Pauline: And also I’d like to just, if I could take that, that as an organisation we didn’t walk out our mother’s, as somebody said to me recently, and on to a stage, we haven’t been professional since the year dot, but I think what you’ve raised is really valid actually, and I think it’s a really good point, and I would invite you to come and speak to me afterwards because if there is any way that you think that we can facilitate that, or help you and your friends, and all of us that play music in that way, to make that point of view and that experience known and validated, then I personally would be very happy to facilitate that.

Úna: If it’s a cultural thing within the music that is not professional, I plan to put these in a book that people can buy or pick up in ITMA or in the library, and at least if we read them all, all of these anonymous stories, that from my point of view we hope for a change. Muireann.

Muireann: I just after listening to you there, and I can relate so much and I think a lot of us here have come through, like, what is professional? You know? Are we up on stage fulltime, or are we part-time, do we do the odd session for a few quid, do we teach? Let’s take the word professional out of it for a second, just talk about respect for each other, and personally if I went to the guards every time someone grabbed my arse or whatever, I’d be living there… so I’m not going to take that course of action, just not. But what I hope will come out of this, and the reason I’m supporting FairPlé is that I feel conversation is so important. This is the first time I’ve ever spoken about this. I’m in a room full of people that I know are probably in a similar situation, and now we’re talking and now it’s a conversation and this conversation will filter out there, and maybe people will rethink their actions, and that’s what I hope will come from all of this.

2nd Questioner: It was much the same thing, that I kind of felt the same way in the beginning but then I started to realise that I mightn’t feel like a I’m a professional musician but I often get paid to play music so how do you define what is a professional musician when a lot of us are working a couple of jobs, or doing different things, so I think that’s another discussion that kind of needs to happen, especially with my age group because I don’t think very many of us are fulltime musicians, but a lot of us are definitely doing it part time.

Kate: Really just… one really practically thing that I saw, and I think I flagged it on our Slack group, was in Birmingham, was a movement between some of the venues and people who are putting on acts, because there, there’d be a lot of bands, not traditional as such but it’s a lot of bands, like me, I’ve always played in the evenings, I’ve always worked fulltime and that’s … my life in music is outside my work, so they’ve clubbed together and started a campaign to say, I can’t remember what the actual slogan was, but it’s basically they have stickers in the venues, the staff are all briefed to say no it’s not acceptable, so that every musician in that place knows that they can approach those staff, and it sets a tone, and it’ll take time, it’ll still …..things will still happen but people won’t necessarily go to the police with stuff, it just happens so frequently, you wouldn’t. But at least it means you would feel comfortable going up to a member of staff and actually saying this happened, it’s not acceptable, can you just get rid of that person?

Speaker from the floor: Sorry just to cut in, I think that campaign was ‘Ask for Alice’ or something like that. So instead of going up to the bar and saying someone’s harassing me, you can go basically go up to the bar and there’d be signs up, and they say "Oh sorry come here, is Alice working tonight?" And it’s a code to say you know, can someone come down and help me out, without having to point to someone down there you know, which people are obviously not willing to do.

Kate: It’s quite similar, I think what I liked about it was that it recognised that those people are working and they are being professional so it’s an extension of that idea to actually recognise that they are people who should be respected because they’re there to provide music for the evening and to recognise that they’re not just there for the good of their health.

Another speaker from the floor: Thanks. I suppose picking up on some of those discussions, one of the reasons I’m here is to be more involved, but also when someone is brave enough to come forward, how do you – it’s not just to enough to listen, I think Pauline, you were saying, how do you respond. I think going back to Muireann, for all of us to be able to respond when somebody does come to you, I think that something that we need to filter out, as much as the message of being able to bring it forward, that we can all respond, help each other, do… but it’s how do we do that?

Pauline: That’s a very good point.

Úna: Do you want to answer that?

Pauline: I guess I have no direct experience of people responding well to it because the times in my life where I have flagged it, the response hasn’t been great, to be honest, it’s just been very awkward behaviour and I’ve always felt that my flagging of it has been an inconvenience. So I mean I guess for a start, believing the person, or at least behaving like you believe them and being willing to take it to the next level. But I guess in our profession, where or who is that, so in my case, when I was on the bus, there was the bus person who owns the bus company, there was the promoter, who had three different bands over there, there was the people within the band that I was in, that had kind of formulated or configured that line-up of musicians, and I mean I don’t have the answer to that. I mean on a personal level I suppose with care and intent to go and sort this out, and if needs be go to the relevant authorities or support systems. But I think on a professional level, as we just discovered today, we have to establish who and what those people are. Sorry I’m bad with the microphone, you’d think I’d know by now

Niamh: Sorry I’m not sure there is an answer to this either, but one of the things that struck me, and getting back to what you were saying Pauline earlier, about the fact that you know, if we do say something, we’re very much fearful of not getting future work, and you were talking about for example that there are people responsible when you’re hired, and that the buck rests with them, but I think a huge factor in the nature of our work is that it’s always a different person, so it’s your future work you’re worried about. And I don’t know how we tackle that, but I think it’s not just a question of people believing somebody when they voice this, but future like employers all across the board, I’m talking about festival programmers, festival organisers, if they’re told somebody is awkward please question that.

Pauline: Yeah that’s very true Niamh.

Niamh: Question that statement, you know because it is the future work we’re worried about and it’s the transient nature of our work and the lack of protection.

Pauline: And that tag goes around and like it has to be said, "Oh she’s awful awkward" "She’s very quare, that one" "Oh Jesus don’t, she’ll cause a fuss" but there’s loads of men who are as awkward as they want and it’s even an advantage sometimes because he knows what he wants. Well we know what we don’t want. You know, and I think that tag is really damaging and we were talking about it last night, so when that’s bandied about we have to be very careful about why we’re saying that and what that person who is awkward has experienced or gone through to make them assertive, confident.

Ellen: We also need to be the bystander, you know, because we witness some of this as well and it’s important for us to support the person that we see being the victim of this type of behaviour and I think the more we do that, the more we break down and blame the perpetrator not the victim. So that the person who is the victim - you’re not afraid "Oh I’ll never get another gig", it’s the person ... but you also said that there was family and friends, and people know… if people know the person, they’ll know they’re a cad as well, and so it might help to name it.

Úna: We’ve three minutes left. Is there one more question … Tóla?

Tóla: Sorry to… I think it ties into something that really scares me about our industry which is the celebration of mental deviancy, where ... basically where people go to a gig to see somebody explode, to misbehave, and it’s something that really scares me in the thing I love the most. That you hear coming back, ‘Oh my God, you should see this person last night, they were so crazy’. If they were an accountant they wouldn’t be working. And it’s something that I think we need to call out a little bit more. And it’s the same, the girl who talked about the more session-y situation you know, it’s that wink and elbow thing, "Oh he’s such a character" "He’s great craic", OK you know, we have to think "I have the strength of character to kind of go 'Eh ... listen mate, that was awful you know.' " I love what the first day’s panel, one of the speakers said, which was… he was talking to men, because you know this is about women, but it’s about certain ways we can help too.

Úna: Thanks. And I think Ellen raised a really interesting point about quotas, there’s a lot of stuff online, from women as well, saying if there are quotas involved in this, we’re not going to know why we’ve been chosen to be on stage any more. So it was something I wanted to discuss, and I think it would be great to discuss it over coffee. I know it’s something people felt really strongly about.

I’m going to give the last word to Pauline, she wanted to say….

Pauline: I just wanted to say one more thing, in that, just as a founder member of this organisation, the professionalism thing is something that has bothered and troubled us greatly because we do not want to distance ourselves in any way, by merit of a pay cheque or two or three or whatever from anybody else. It’s not a professionalism organisation, it’s a women’s organisation, and it’s a women’s movement, and it’s a feminist movement, so if you have any concerns about whether it is for you or we are representing you, or misrepresenting you in any way, please do come and talk to us about it because we are only as strong as the people who contribute and give back to us, and we’re trying our very best for volunteers to cover all bases, and we’re not getting there, but we really would like to. So all contributions and approaches by all interested and invested parties are so welcome to us because we’re about inclusivity rather than exclusivity that’s all I wanted to say.

Úna: From women and men.

Pauline: And men of course yeah.

Úna: Thank you.

Transcribed by Niamh Parsons.

Proofreading and editing by Úna Ní Fhlannagáin.