PANEL 1: She Means Business - Making Music Work

Saturday September 8th 2018, 11:45am - 1pm, Liberty Hall, Dublin

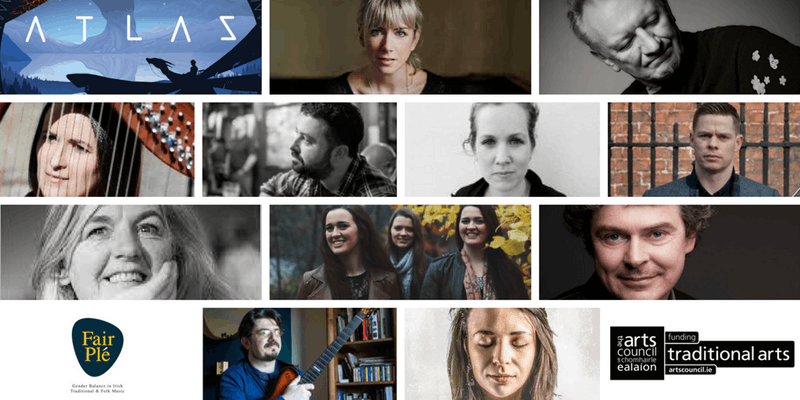

Panellists: Eleanor McEvoy, Peter Cosgrove, Liz Doherty & Dermot McLaughlin.

Chaired by Lynette Fay.

A panel discussion with industry professionals to evaluate the role of women in the business of Irish traditional and folk music. We discuss how musicians and performers negotiate the politics and practicalities of creativity, touring, recording and earning money through art. Through the lived experiences of these panellists, we examine the questions surrounding women in Irish music and the conditions that lend themselves to a largely male-dominated industry.

Chair:

Lynette Fay is an award-winning presenter and producer, working across radio, television and print media. She specialises in music broadcasting and has championed the promotion of Irish traditional and folk music throughout her career. She currently produces and presents BBC Radio Ulster's flagship traditional music programme Folk Club.

Panellists:

Eleanor McEvoy achieved star status in Ireland in 1992 with her song “A Woman’s Heart”. Her critically acclaimed canon of work spans 13 albums and she is today recognized as one of Ireland’s most successful singer-songwriters. She is the current chairperson of IMRO.

Liz Doherty is a traditional Irish fiddle player and renowned teacher. Winner of Ulster University Students' Union 'Inspirational Teacher of the Year Award' (2017). She currently holds the post of Irish Traditional Music Lecturer at the School of Arts and Humanities at Ulster University in Derry. Liz has worked and continues to work as a consultant and advisor within the traditional arts sector and has conducted various pieces of research for national and European bodies. She has recently been appointed to the Expert Advisory Committee of Culture Ireland.

Dermot McLaughlin is a renowned exponent of Donegal fiddle music. He learned from Donegal fiddle masters including Con Cassidy, James Byrne, Francie Mooney, Dinny McLaughlin, Vincent Campbell, and Francie Dearg Ó Beirne. Dermot usually performs solo and unaccompanied, which is unusual in Irish traditional music these days. He also teaches at summer schools, masterclasses and other events and prefers to work with small groups or individuals

Peter Cosgrove is an expert on future trends and founder of the Future of Work Institute in Ireland. He is a regular media commentator on gender diversity in Ireland and is on the steering committee of the 30% club. He is founder of the future of work institute at Cpl, Ireland’s largest recruitment agency.

TRANSCRIPT

Lynette: Bhuel, sin muid – and just for the record, can I point out that we are beginning one minute early? I don’t think it’ll ever catch on, no… I’m just terrified of my life of Síle Denvir, that’s all. Móran beannachtaí daoibh, a chairde, agus tá fáilte romhaibh chuig an seisiúin cainte seo ar maidin. Agus caithfidh mé a rá go pearsanta go bhfuil lúcháir orm a bheith mar chuid den phlé, den chomhrá, den lá agus den deireadh seachtaine seo, 'Rising Tides', atá againne. It's an awful privilege to be part of what I think will be a very enlightening weekend, a weekend of connections - I think it already is - a weekend of open debate, and discussion, and most importantly, I think, a weekend of insight. And I hope that we can learn from each other either in the formal context - what happens in this room - or outside in the coffee bar, or elsewhere.

While I'm here to chair the debate - is mise Lynette Fay, by the way - I'm Lynette Fay, from Co. Tyrone, I'm a broadcaster, primarily on BBC Radio Ulster - I have a vested interest in making music work for women: I am a woman. And I thought, through the world of media, "I work in music, and it is my business!". I work across radio, television and print media, online as well, and I also left a staff job in the BBC a number of years ago to work as a freelancer and to become self-employed. So I hosted my first radio show of 2018, this year, on New Year’s morning and I remember remarking that day that 2018 was going to be the year of the woman. Now I mentioned this because the centenaries were coming up, you know - one hundred years since the suffragettes secured women’s suffrage (albeit limited at the time - I think that was over-celebrated, to be honest). One hundred years since Constance Markievicz became the first female M.P. at Westminster, etc. And then came the #MeToo movement: none of us could have foreseen how that would have changed things. Even things like the Irish women’s hockey team doing so well this year really highlighted women, the role of women, what they can achieve because they put their minds to it, get together collectively, what can be achieved as well. And then you realise just how under-funded they are, how under-supported they are, and hopefully their success will lead to that changing as well. Just a matter of weeks ago - I think this is relevant because we’re here in Liberty Hall as well - I was working on a documentary about the first Civil Rights march, which wasn’t in Derry on the 5th of October by the way (sorry, this seems like a history lesson, but it’s not, it will be relevant!), the first Civil Rights march was from Coalisland in Co. Tyrone to Dungannon in Co. Tyrone (I’m from Dungannon in Co. Tyrone). And while I was researching this documentary, I learnt that there were a group of women who had been living in slums and condemned houses in the 1960s in the North, now this was prevalent all across the North, they were nationalists, they were Catholics, and they took to the streets with their children in their prams in an effort to impress upon the majority Unionist urban council - and subsequently the Northern Ireland government - that they had a right to better housing. They called themselves the Homeless Citizens League. They weren’t involved with any political groups, any organisations, they were just women, they were mothers who demanded a change in the face of injustice. And out of their efforts came the Campaign for Social Justice, and out of that grew the Civil Rights Movement. All those women asked questions of the status quo and they acted, so they ‘meant business’ just like FairPlé 'means business!'. So I thought that was relevant to mention today.

So what does this mean in 2018 for women who want to work successfully in folk and traditional music, that’s going to be our topic. ‘She Means Business, Making Music Work’ is what we’ll be talking about for the next hour or so. And to break this down and to have as complete a discussion as possible within the timeframe we have, we’ve invited an expert panel to join us. Now I’ll introduce them individually, each speaker will address the audience for about ten minutes or so, and then we have a further short discussion amongst the panel, and then we will open the discussion to the floor. We have a 1pm cut-off point (Síle’s eyeballing me the whole time!) so if you ... we want to keep the discussion flowing, as we hope that will be the case, so we will invite you to take the conversation forward through lunch if need be, but we do want you to get involved, so do listen to everything carefully. If you have an opinion, voice it, if you have a question, ask it, this is a very friendly forum, and at the end of the day, what’s the point in being in here if you can’t add to the discussion? And throughout the discussions today as well, we encourage the Twitterati amongst yous, the Instragrammers, the Facebookers, to relate what’s happening here in Liberty Hall to the wider audience as well - please use the hashtag #FairPlé or the hashtag #FairPléRisingTides.

So I think that’s about all the business end of it covered and our panel are assembled here. We have Eleanor McEvoy, Peter Cosgrove, Liz Doherty and Dermot McLoughlin, and we’re going to introduce them individually and then each will talk to you for about ten minutes.

So first up, I would like to introduce songwriter, singer and musician Eleanor McEvoy whose cannon of work boasts thirteen albums, and one of the biggest selling Irish singles in history, "A Woman’s Heart" - don’t sing it, I don’t think she would thank you for that. Eleanor is currently chair of the Irish Music Rights Organisation, IMRO, so what better way to hear about making music work than from a woman who is at the heart of the Irish music industry. Please welcome Eleanor McEvoy.

Eleanor: Thanks a million Lynette, well I think that if we were to sing it I’d say there’s some amazing voices so it would sound pretty amazing but there you go. I’m getting some work done in my house at the moment, some building work, and two days ago, a guy came in and he wasn’t Irish, he didn’t know me, and he wouldn’t have known my name or anything, and he saw the guitars and he said ‘Oh, your boyfriend plays guitar?’ and … he was a lovely guy but I get that a lot, you know, and it’s something – I’ve told this story a couple of times as you know, I walked into a guitar shop one day and I went to get guitar strings and the guy behind the counter said ‘Oh, do you want them to make jewellery?’ and I said ‘No, no I’m going on the road for eight weeks, I need 30 sets of strings, that’s why I need them.’ . But you get that a lot, and it’s not malicious, it’s not nasty, it’s subconscious. And I’m 51 years of age, you know, I’ve got, I don’t know, 15 albums to my name or whatever, like at what point ... ? I used to think when I was younger, "No, Eleanor, when you prove yourself, when you make your albums, when you get out there when you’re gigging, then they’ll - then people will know." But they don’t, society doesn’t seem to move on, it doesn’t seem to change. There seems to be roles that are acceptable for women to perform; you’re allowed be a singer, I think we’d all agree with that maybe; you’re not really allowed be a composer, you’re not really allowed be a producer, you’re not really allowed be a sound person, you’re certainly not allowed be a musical director if there’s a guy in the band. If it’s an all-women thing, you’re allowed be a musical director. So you have to ask - why are we confined to certain roles, and why are certain roles prohibited to us? G.D. Anderson said that feminism isn’t about making women strong, women are already strong, it’s about changing the way that the world sees that strength. And that really is what I want to focus on. We have to change the way society perceives our strength. We don’t need to make us strong. We don’t need to make Karan strong, we don’t need to make the guys here in FairPlé strong. My God, look at the strength, look at what they have done, I nearly fell off the stool when they said it was only seven months ago. Look at what these amazing women have done in seven months. We don’t need to make them strong. What we do need to do is change the way society perceives them. One thing I do a lot when a guy says to me, "Look I’m not sexist, I’m not sexist" - and it’s not just guys, it's women can be sexist too, society is sexist, we’re all susceptible to it ... there’s a story I tell and it’s this, a man is driving along in a car and he crashes and he’s got his son in the back of the car and the man crashes the car and is killed, and his son is brought to hospital and when the son gets to the hospital, a surgeon looks and says ‘I can’t operate, this is my son’. I’ll run over that again, a man is driving along in his car and he crashes the car and the man dies instantly and the son is brought to the hospital. When the son is brought to hospital the surgeon looks at the son and says ‘I can’t operate, this is my son’. People will say the most extraordinary things when you tell them that story. They will say to you the son was a twin that was adopted and he was separated at birth from the other twin, or they will say the egg … there was an egg that was fertilised by two different, you know, they will come up with extraordinary things as to make sense of that, what they call a riddle. It is unbelievable that given that there’s 7.6 billion people on the planet, and any child ... there’s only two people out of those 7.6 billion people that can look at that child and say, "That is my son.". One is the father and one is the mother. So when you take the father out of the equation, and the only logical solution is that it’s the mother, it is still more likely to some people that there was twin who was separated at birth or that one was an adopted father and one was the real father, and that is still more likely than it is that you have a woman who’s a surgeon. Now a lot of that is not malicious and I’m so sorry for the abuse that you have suffered at the more malicious elements but really I’m concentrating on the good guys out there who don’t mean to be sexist, they just are. And I think that that is a very important tool for you to use, you know, throw into a dinner party or into a dressing room you know, and just … when somebody says they’re not sexist you know leave them for a couple of hours, throw in the story and see what the responses are.

Logic goes out the window when you’re faced with prejudice, I think that’s one of the main things you can get from that story. That there’s a logical solution, but logic doesn’t occur to you when you’re looking at prejudice. And people who believe in equality and people who are very strong on issues like racism, you know, don’t bat an eye when they’re faced with sexism. People who are marching you know for apartheid in South Africa etc., rightly so, they’re not doing the same for feminism. When a woman’s paid less, it’s not as bad as somebody who’s, you know, a different colour being paid less, that’s outrageous, but a woman being paid less, not so much.

Why are we undervalued as women? Why? I don’t understand it. And it is to do with the perception. And I think that that’s why we need this paradigm shift. I took great solace from Madeleine Albright’s autobiography, I don’t know if any of you read it. But she talked about women, how it was important to interrupt, that she teaches her female students to interrupt, she’s the former Secretary of State in the US. And one of the things that she had in her book, was she found a list – a "To-do" list. And on the list was, you know, "Ring the King of Spain, talk to the President about this, that, buy low-fat yoghurt" and I don’t know why that made me feel more worthy as a person because I would have lists like that all the time, you know do this, check the mix on that, you know, talk to such and such producer, do this, you know buy the low-fat yoghurt and put my list of things down. If I was showing that list to somebody I’d kind of be ashamed of the low-fat yoghurt, I’d be ashamed of the domestic stuff, because for some reason when I’m working I feel like I have to pretend like I don’t have a family and yet when I’m at the school gates and I’m being a parent, I feel like I’m ashamed of my work, I feel like I have to pretend I don’t have a job. Why is that? Why did I feel like that, why do I feel guilty in every turn, and you know that I’m not doing each job properly, I don’t know, but I do. And we don’t – the same thing doesn’t seem to happen with our male colleagues. I was in – I happened to end up in a dressing room with Muireann, I don’t know if Muireann is here, sorry Muireann, a while back, maybe two years ago, and the conversation ended towards the … went to the juggling we were doing with the children on the road, you know handing them over at services stations, and in airport lounges, M50, and M25 in London you know, all the stuff that you do. And it was funny in all that time, despite all the wonderful, wonderful male musicians that I work with, I never had that kind of conversation in a dressing room. And it’s just ultimately we feel we have to carry the ultimate can for our domestic life, whilst wanting to be the ultimate professional in our professional lives. So I think we have to understand what our strengths are, because we are very, very, very strong, and I have to say you know I’m on two boards now, I’m on the board of the National Concert Hall, and I’m on the board of IMRO. So you know recognise our strengths and help society alter our perception of those strengths. Thanks very much and I know there’s going to be questions at the end, so I’ll hand you back to Lynette.

Lynette: Thanks very much Eleanor, so I hope you’re stocking your questions as we go along folks, and keep the tweets going as well, there are a few – so #FairPlé, #FairPléRisingTides as we go along.

Now our second speaker is Peter Cosgrove. Peter is founder of the "Future of Work Institute - Ireland" at CPL, which is Ireland’s biggest recruitment agency; a regular media commentator on gender diversity in Ireland; and Peter is also on the steering committee of "The 30% Club", which is an organisation which aims to develop a diverse pool of talent for all business through the efforts of the chair and CEO members who are committed to better gender-balance at all levels of their organisations. Peter is an expert on future trends, and will now present his take on "She Means Business, Making Music Work". Please welcome Peter Cosgrove.

Peter: Good morning everybody. There was a country a long time ago that elected its first female Prime Minister. Unfortunately when she was Prime Minister she was constantly referenced for the clothes she wore, the shrillness of her voice, the amount of cleavage she showed, her marital status. And then on top of this you’d have media commentators using words like ‘witch’, ‘unproductive cow’, ‘bitch’ which had never, ever been attributed to a male Prime Minister. On top of this again, her father died during her term - and when her father died, one media commentator said "Her father probably died of shame" - which was horrendous at the time, but it was just to highlight that along with all the gender challenges she had, she had to deal with all the regular political insults that any politician has to deal with. Now I lied when I said this was a long time ago - this was 2011 to 2013 and that was the Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard, who was the first Australian female Prime Minister. Her male counterpart, Tony Abbot, was regularly seen holding signs with ‘witch’, ‘bitch’, ‘cow’, and he became the next Prime Minister. And the only positive around this story is she literally eviscerated him in the Houses of Parliament, which you can watch on YouTube, at the end of her term. But the interesting thing was when they asked her "Why didn’t you say anything, why didn’t you do anything?" and her comment was "Because I was the first, and the problem with being the first is I’m not representing myself, I’m representing all women, and if I’d said anything it would have been the usual, 'You can’t hack it’, ‘I knew she couldn’t do it’, ‘You see what happens when you hire a woman to do a man’s job’ etc. etc. And no man has had to have this, men don’t do these jobs, and are almost never the first."

So I want to talk a little bit about the role of men in the debate, because I’ve talked about this topic for years and one of my biggest challenges is you regularly talk to a room full of women who already know all this and actually what you really want them to do is let them leave and bring in a male guy instead of them to actually listen to this. I’m on the steering committee of The 30% Club, which is all about balancing boards in businesses and senior management in business. And when we do talk to businesses we talk to them in business language; we say "Here are four reasons for diversity. The first one is profitability, companies have been seen to be more profitable when they’re diverse. Sounds like a good reason. Number two, talent: guess what? 50% of world is female, and talent is a very hard commodity to get, and it's amazing when you get the best people in the room; wouldn’t you want to be focusing on a 100% of the population, not 50%? The third reason is innovation. Some of the most innovative companies in the world now, AirBnB, Facebook, Google, you know, didn’t exist 30 years ago, and it came because of somebody’s brilliant idea, so diversity breeds innovation. And then the final one, which again is about our customer base, we aren’t an Irish company anymore dealing in Ireland, we’re dealing around the world. So of course our global customers aren’t all like us, so if we all look the same and act the same, we’re going to really struggle with a global customer base. And these all seem like good, reasoned arguments, but they don’t make much of a difference. In Ireland, the boards of Irish …. boards for women have gone from 11% to 13% in five years. In the UK they’ve gone from 11% to 27% in the same time, and I’ll tell you why in a little bit. But when we talk about this, I have ... What I hear from men is two things, because they go "This is nonsense, it’s just the best person for the job, it should just be a meritocracy, and I don’t know what all the fuss is about and actually everything seems to be about women at the moment, not men.". And it’s crazy but you will hear this a lot and actually a lot of this comes down to education and the right communication, because if you get the communication wrong at the start, everything else falls apart.

So the first thing I’ll always say is I’ll talk about privilege, and the reality is privilege is invisible to those who have it and men are the beneficiaries of the largest affirmative action programme in the history of the world, it’s called "The History Of The World". So men need to understand we’re starting at a rigged deck. There’s a famous story about a teacher who, to explain privilege, puts a bin in front of the classroom here, and says - everybody, imagine you’re all students - gives you all a piece of paper and says "Crumple up that piece of paper, throw it in the bin, if you hit the bin and you get it in the bin, you go to college, if you miss the bin you don’t go to college". Now, not surprisingly, the kids at the back of the room put their hands up and says "This doesn’t seem very fair." Bizarrely, nobody in the front of the room says anything, they go "Shut up, we’re in the right seats here.". Now you’d like to think the people at the front should go "Maybe we should all stand in the middle and maybe we should all throw the same piece of paper", but they don’t do it, because people either don’t know they’ve privilege, or they do know, but they like the fact that they’re in their position. So the men have that because the CEOs are filled with men, senior management is filled with men, so it’s a lot easier to hire men, and know men like themselves.

The second reason is culture; if you ask men, women as well - name who your top five friends are. So think for a second who your top five friends are. People think "Well, they’re not family members, friends" and then say "Right - now look at the categories of age, sexuality, race, religion." And actually if you go through all these demographics, you’ll realise that they’re not just a little like you, they are incredibly like you. And this is one of the challenges as organisations. People hire people they know, and people that are like them, so if lots of people look the same in organisations, whether you like it or not, they continue to hire people like them. We do it with our friends, we hang around with people who are like us. We don’t mean to, this is just a little bit more comfortable. We find it a little bit more challenging when we deal with people who are very different to us, because we struggle a bit more, and that’s just the nature of it because you know you’re not as used to dealing with people who are different. But if you look at most cultures the first time we realised we were different was when we travelled. You went abroad, you realise people ate differently, they talk differently, they might shake hands or greet you differently, and suddenly you realise when you’re in a minority, in a different country that you feel quite out of place. And in organisations, there is a dominant culture. The dominant culture is usually white, male, Christian, married, and if you’re married, it’s married with kids, it’s able-bodied, it’s university degree versus not university degree, this is the dominant culture, it doesn’t mean everybody in the company is this, but if you’re in this, you’re part of a herd and it’s a lovely place to be, and let's be honest, we all like to be part of a big group. But what we need to be aware of is people who are outside that group, and it’s not just women. People often ask me ‘Peter, why are you always taking about gender diversity, there’s loads of other diversities out there.’ There is, but guess what, gender diversity is one you can solve really quickly because it’s a 50/50 split, and secondly you can see it, and finally gender diversity and all the other diversities actually follow the same process because a lot of becomes how you think about it.

And then the third one is around unconscious bias and the key word here is unconscious because a lot of people say "I don’t have unconscious bias" and you have to explain to them the word unconscious. National Geographic ran … National Geographic, you all know the magazine, they ran a program for people and they said "Why are people running away from some hurricanes quicker than other hurricanes?" They did all the research and they found one of the reasons people ran away from hurricanes quicker than other hurricanes was if you had a male name versus a female name. This was men and women, so remember men and women are equally biased around things because of how we grew up and the patriarchy in society. Seth Stephens wrote a book recently called "Everybody Lies" it was all about Google and trends in Google and he said parents will google twice as often "Is my son gifted?" than "Is my daughter gifted?" - but this is men and women, because this is the society we were brought up in. So when people start saying things like "It’s a meritocracy" they don’t realise there’s so many implicit biases that we have. This happens, and the most famous example is within the music industry, where only 3-5% of women forty years ago were in the top orchestras, and there was a lot people saying "Well, you know, we interview everybody, there’s a lot of women coming out of college but actually when it gets to the orchestras maybe they just can’t hack it because you know we interview everybody and it’s just all men.". What did they do? They just put a blind between the interviewee and the interviewer and they actually told women not to wear high heels or perfume so there could be absolutely no doubt who the person the other side was. And within years, I mean years - sounds like a long time, but it’s relatively short - it was tripling the amount of women at the top orchestras, and the split is much narrower now. But nobody interviewing would have ever said they were biased. And one of the interesting points is composers are still 98% men because you can’t have a blind audition, right? So we need men to get involved in this debate because actually when they look at a lot of these things like privilege bars, they don’t realise when they say things like "It’s just the best person for the job", all those people interviewing those musicians, both men and women would have said "But I don’t have bias against men or women" but they clearly do. Because when it’s blind, they see a difference and that’s what we need to look at.

So what can we do about it? Well I’ve got two kids actually, I was just thinking about my kids, and they’re both home-schooled, they’ve been home-schooled all their lives, because I love education, I’ve looked at the best way to educate my kids and I realise rather than going to school, for academic and for socialisation, home-schooling has been the best way by a mile. That’s not true. but I just want you to ask yourself for a second - when I said that, did you go "Home-schooling, oh, that’s interesting, let me hear more of that!" or did you go "Home-schooling? That’s bollocks!". Now - I’m taking from the room that quite a few of you said that. Now here’s the point: there is a serious point here. If you did say that, you then stopped listening, you completely stopped listening. So the problem with diversity, it’s not just about diversity of colour, race, creed, gender, it’s diversity of thought. We approach everything from our own point of view. So I’ll hear lots of women going "Gender quotas are nonsense.". Now it doesn’t matter whether you agree or disagree but often people’s views come from "I didn’t need it to get here therefore no one else needs to" - well, hang on, maybe you won the genetic lottery or maybe you won the biological lottery that you’re incredibly resilient and you got here or you had amazing parents who got you here, or you had the worst parents ever which drove you to get to here, but not everybody is you and lots of people have different views. But the most important thing is walking a mile in somebody else’s shoes which is really difficult to do, but for me it’s the first stage of diversity. The second, and probably most important, is making it personal to men. In organisations men have daughters, nieces, sisters, mothers who they care - and hopefully a lot - about, but often the role of how they would want their daughter to have everything in life, is completely different than how women are treated in organisations. So don’t talk about women, talk about people who matter to them. People are very different about people who they care for, as they are with data and women in general, you need to change the debate.

And the last thing, we do need government support, I said the UK went from 11% to 27% because they had the Lord Davies Report that they brought in that started shaming companies into having more women on boards. And you do need a stick approach, it just won’t be a carrot approach, you just do need a stick you know. Leo Varadkar has recently brought in the same thing in Ireland called ‘Better Balance for better Businesses’. It’s only begun, Bríd Horan and Gary Kennedy are leading it for business to actually build this, because you do, as someone said earlier, you cannot be what you cannot see, so you need to get the numbers up to a certain level.

There’s two last things. There’s a problem still, there’s a huge social stigma, it’s already referenced earlier. Countries like Switzerland and Germany still call you a "raven mother" if you come back to work too quickly after maternity leave. Men never get asked "How are you balancing your work and your fatherly duties?". It doesn’t get asked, right? So Anne-Marie Slaughter, who was very high in the government, in Obama’s government left because her 15-year old son was very sick, and people started pilloring her in the press, going "I can’t believe you’re leaving." Now ... the same reason as Julia Gillard: she was a woman and she represented all women. But no man would have got that, they would have been called a superstar for taking time out of work to do this. And her view is: in the way of trying to get women to be and do everything, we have completely negated changing the role of men. So all we’ve done is we’ve told women they can everything, but we’ve changed none of the social structures or constructs to give them that opportunity to do it, because guess what, men aren’t changing anywhere near enough, so we need to get them involved in the debate. So let's not do this because it’s right for business, it's right for Ireland, let's just do this because it’s the right thing to do. Thank you.

Lynette: An awful lot of food for thought there - thank you Peter. I just wonder - anyone who, regardless of gender, who googles "Is my son gifted?" really needs to take a look in the mirror. Anyway, on to our next panellist who is Liz Doherty, and Liz deserves a round of applause, because she came here from Derry this morning on a four-hour bus journey. And look at her, bright and sparkly as ever. Liz is Donegal fiddler, teacher and lecturer of Irish traditional music at the Ulster University in Magee in Derry. Last year she was voted "Inspirational Teacher of the Year" by the Students Union, that’s no mean feat. And she also works as a consultant and advisor within the traditional arts sector and has been appointed to the expert advisory committee of Culture Ireland. Liz is the embodiment of the woman who ‘means business’ in the world of traditional music and we’re delighted that she’s here with us today – Liz.

Liz: Hi, everybody, how are you doing? Thank you Lynette, and thank you to Karan and all the team at FairPlé for inviting me to be here today as part of this conversation. I have no timer with me Lynette, I’m actually going to carry out this under, way under, the ten minutes because I’m sure there’s lots of interesting conversation to have so. But - famous last words, once I get started it could get hard to shut me up, so feel free to throw things if it comes to that.

So yeah, I’m from Donegal, I’m a fiddle player. I’m also an academic, I’ve been working in academia since 1994, I’ve kind of been around this game for a long time. I’ve also been on boards like ITMA, been involved in the Arts Council, and I’m involved in Culture Ireland and certainly for me over the years, back in the nineties when I sat on my first board, I kind-of, even at that stage, had the realisation that I was the sole woman often at that time, and it’s great for me to see that has changed quite a lot over the years where there’s many more females on these boards as well. So it’s definitely small steps moving in the right direction but we’re certainly not there yet. For me I guess I’ve had … I’ve been a performer, I’ve been in bands where I’ve been the only female in the band, I’ve been in all-female bands, I’ve had the whole range of experiences you know that Eleanor talked about as well, and always kind of that thread, that story going on in the background about "Well, what is the craic about being a female in this world of traditional music?" When I started lecturing in traditional music in Cork, back in the nineties, I introduced a module, it was my very first one that I set up, it was called "Women in Traditional Music". And I had a conference, held a conference in 1995 in U.C.C. about women in music in Ireland and I had composers, Eithne Ní hUallacháin came down, we’d Máiréad Ní Dhómhnaill, Eibhlís Farrell, and gathered a whole raft of women together. And it’s interesting looking back that early in the game for me, that already that conversation was very much at the forefront of my mind.

So there’s two things that I do want to say today. The first one is that - brilliant that all this conversation is happening and brilliant that all the spotlight is on women, but it is important that - the women are kind to the women. It’s really important, because, let's not lose the run of ourselves, sometimes the damage is done by women to other women, and I think it is because when women maybe do break through that glass ceiling, they’re so relieved to have got there into positions of power that they’re going "Ah, thank God, right I’m sorted." And they close the gate on other women coming behind them. And I love the "Shine Theory" from the Obama administration, where you know the women made a serious commitment to supporting each other and shining the spotlight on each other and magnifying their ideas and themselves and that. And it's really important that we continue to do that because we all need to work together to make this world of traditional music a better place for all of us. So keep that "Shine Theory" very much in the forefront as well.

The other thing I guess, and in my conversation with the FairPlé team over the last while, I’ve been obviously concerned about things like where women come into the industry again. I was a player quite a lot in the 1990s and into the 2000s, and then when I started with the Arts Council I took a, very much I think a female guilt trip, going "Oh, I can’t be seen to be funding festivals and then performing at them.". No man in the Arts Council ever thought like that or ever had that guilt trip I did. And that was probably just a really, I don’t know, was that a female reaction or whatever? And I kind of brought myself out of the playing game, and deliberately at that point. After that then, I went on and had a couple of kids, and to be honest, kind-of whatever, 15 years on, I don’t think I would have a clue how to get back into the industry if I wanted, I wouldn’t know where to start, I wouldn’t know if I was relevant any more, if I had a place there? And that’s really started to bother me this last while, you know - if you take a step out of it, how do you come into it again? And that then led me to the bigger realisation that actually part of the problem, and that maybe frames this conversation around where women fit in is – what is this profession of traditional music? Do we actually have a profession? We use the word; we want to, you know, present ourselves in that way. We are professionals on lots of levels but I think we’re still missing a vital piece of infrastructure that allows us, male and female, to properly present ourselves as professionals in this space. And I see lots of opportunity for the women to take the lead on making the profession of traditional music much more coherent, much more positive going forward. We need structures, we need supports. You know, self-doubt crippled me for years, every time I went on the stage I was throwing up before it from the nerves, the crippling self-doubt and all of that. And women often experience that, especially when we’re fewer in numbers - we wonder "Am I, you know, good enough? Am I relevant? Can I do this?". So the support, the structures, the agencies, the agents, the managers, the means, the guidance, the mentors. I do work with an organisation that’s London-based at the minute called "Aspire", and it’s trailblazing women and I’ve worked quite closely with them over the last couple of years to help me be a better mentor, because obviously in academia I’ve been working with students, guiding them in their careers, but to get a bit more insight into women leaders and how that can happen, and it’s been a real revelation. And I would love to see that kind of work happening within the traditional Irish music world and our community as well. Because often within our sector at times I do fear that we are in danger of eating ourselves. We’re happy to undercut each other, the next gig sometimes is all that’s important, rather than looking long-term, looking at our strategic position. And this is men as well as women, women as well as men, it’s for all of our benefit, all of our good, to figure out how we’re going to move forward. Everybody feels that they have to re-invent the wheel. Somebody organises a conference, somebody else will come in and offer a conference on the same theme that will happen, you know, a month later. Somebody wants to put a database together, somebody else will come in and do one. And people are torn then, are you with this crowd, or are you with the other, all those factions, that kind of do represent a lot of our arts world are present there in traditional music as well. So instead of us all feeling that we have to re-invent the wheel, surely we’d be better to do exactly as what’s happening with FairPlé, is put the heads together, is somebody already doing it that we can all get behind and make it better. Think strategically, can we make the traditional music sector as a whole stronger for the benefit of all, and that’s where I think we can shine, not only as females but for everybody who’s part of our community and make the traditional arts the strongest that they possibly can be going forward. Thank you.

Lynette: Very much worth the four-hour journey, thank you very much, Liz. Now to a Derry native: Dermot McLoughlin, another exponent of Donegal fiddle music. He has been taught by some of the greats including Con Cassidy, James Byrne, Francie Mooney and Dinny McLoughlin, but most of you in the room will know all that. But Dermot has also, for 30 years, had a wide experience in management, in leadership and has held chief executive positions in the public and private sectors, and he is currently self-employed as a business consultant. So how can women make music work? Over to you, Dermot!

Dermot: So you’ve survived the Buncrana accent, now it’s the Derry accent. There’s be subtitles up there for the bits that are too fast. I suppose the first thing I wanted to say today is what motivated me to come along in the first place. I’m driven really by curiosity because I need to know more, and I need to get a better sense of what I can do practically to help improve things and to change things, either through what I can do myself or how I can influence others. And that’s one ... that’s a really selfish reason for coming here, to soak up information and guidance. But I also have a few thoughts that I want to share as well with the meeting here.

One of the things that struck me after I was invited to take part was: I started lessons, and the further on that women go I meet when I teach the fiddle. And I’ve been teaching fiddle classes for a long time, over the last ten years or so, and I’m a wee bit nerdy, like, I keep a note of who’s in my class and what level they’re at when they’re starting and how did they get into music. And I was just looking back over the last ten or eleven years of classes, and I would say at least 80% of the people who are in my classes, which would tend to be advanced classes, so these are people who can play, and what my class looks at is being a musician, not just playing the tunes, so it’s relatively high-level stuff, and about 80% of the people who come to my class are women. And I’m saying to myself: "Where are they? Where do they go?" Because if you were looking at this from an industry or business perspective, you could say there’s a pipeline of serious talent. And look around then, how does this talent normally find expression, that’s gigs and recordings, bands etc. etc. I’m not seeing a correlation with what passes through my, and I know this is just one sample, my sample of fiddler players and what I see out in the world, and I think there’s something there that we could look at, you know.

Part of me is saying there’s a wee bit, not a wee bit, a big bit more research needs to be done about our sector, our industry segment, if we want to call it that, about how it all works. And the reason I say we need more research about it is because I’m highly motivated by the stories that I’m hearing and the opinions, and the real-life experiences that people are sharing about these issues. But part of me is saying "That’s not enough." And part of me is saying "You know, we really need to take a leaf out of the book of 'Waking the Feminists' and 'Sounding the Feminists' and making as much use as possible of the resource organisations that we have." You know the role of the Irish Theatre Institute was really, really important, still is. The role of the Contemporary Music Centre - there’s the Irish Traditional Music Archive - and other organisations who, I think, must have something concrete and irrefutable to offer. The irrefutable bit might be information that "There is blah, blah, blah..." or it might be "We don’t have information." And if "We don’t have information" that surely is a call to action as well, because the more information and facts we have the better, especially these days when things like facts and truths are being assailed from all corners by the barbarians, and we can’t have that. So I do think there’s something – I would love to see emerging from the session today, and maybe the symposium in February might be an augmented research agenda and I know Úna Monaghan has got some research at the minute. But I’m curious myself what is the information that helps account for the sense of unease that’s out there.

And then another part of me is saying "I want to look at that through a lens, but I also want to look at it through the lens of a bigger issue, which is the issue of well-being at individual level - and I suppose at community level - within our world of traditional music". None of the life stories we’ve heard alluded to this morning are pleasant. Some of them are kind-of slightly funny in a "black humour" way, but that wears off after, like, half a second, so it’s not that nice. To me that raises all kinds of alarm bells, the exact same alarm bells that we heard coming from the theatre and other parts of the performing arts sector over the last year or so and I think the good thing is that there’s expertise, people have gone and done things and tried things out and I just hope that there can be a sharing of that expertise and knowledge to help the FairPlé initiative to progress.

And just speaking about the disappearing woman fiddle players, I did a piece of work a few years ago for the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, it was an audit of the traditional music sectors in Northern Ireland and we took a fairly expansive view of what traditional music included, so it was a very wide open thing. And there were some very interesting numbers came up. On a weekly basis there were almost five and a half thousand children and young people doing weekly classes of traditional music organised by 118 different organisations. That’s an awful lot of activity and a lot of young people playing music and although we didn’t tag this in the survey, almost everyone who I interviewed about it said – I asked "What happens after the age of 16, 17 or 18?" They kind of disappear off the radar because no-one has any need to find out what happens. So if they’re in for competitions or for exams there’s a certain useful point at which they’re on the radar, after that they go out into the world. Musically literate, probably very competent, but again my question is, "Where do they go?", because half of them are women and that is not reflected in my view in what we hear coming out on albums or on tour or on festivals. So, but, I don’t know, that’s an assertion. I would love to be able to say there’s an evidence-base that we can consult, that’s reliable and credible, methodologically sound that we have access to, to support the FairPlé arguments as well. So I think more data, more information - can we make insights from it, can we produce knowledge from it, I think that would be a fantastic thing to see coming out from this movement as well.

I was very taken with the points that Peter made and I’m not going to repeat them but I will maybe amplify one point which is the benefits of having diversity in organisations at all levels. I know from my own experience, being involved in organisational development and being involved in board development that there’s a palpable difference for the better in the room and in the quality of discussion and decision-making when you have diversity around the table. And I’m wondering why I have to say it, but I think I do have to say it because we don’t all know that, and maybe we don’t all believe it, but I am telling you that what Peter says is 100% correct. Diversity around the table will make a better organisation and a healthier organisation. If you’ve a better organisation and a healthier organisation you’ll certainly get somewhere if you’re thinking in a big way about well-being. Well-being is good for being effective and productive, therefore profitable if that’s your goal. So organisations really are thinking that way. When you translate that however into our sector, what are we talking about? And what does our industry look like? Well there isn’t any – as far as I know, any useful description, survey or audit of it done in the republic of Ireland, but we all know from our experience a lot of it is, you could say like it’s voluntary / commercial promoters, organisers, festivals are organised in a particular way, there’s not a particularly robust network of touring venues on the island of Ireland so lots of people have to go abroad. But the industry within Ireland itself would probably find it difficult to embrace some of the principles that Peter has outlined, and that I would fully endorse because very often you might be talking about sole operators, or very, very small groups of people working on a voluntary capacity. But that’s not a reason to let them off the hook and I think something’s really important here and Karan referred to this in her prelude to this conference here this morning, Karan was talking about, I think, a code of practice or some code of conduct, or some kind of … maybe a manifesto is a nicer word for it. But it seems to me that if the people who control the stages and the microphones don’t know that there’s a problem, step one is - make them aware of the problem. And that is a really important thing that’s already happened. But that isn’t enough itself because what do you want to change about it, and nobody’s going to change because you tell them. Enlightened self-interest is the key here. So what is a good, credible, authoritative message that we can give to organisers, programmers, producers, researchers, etc. etc. And I don’t have the answers to that, but I’m saying I believe these are the kind of questions that this event and the movement generally should address.

And I think maybe the final thing I would like to say is, from a … I suppose like my relationship with the traditional music industry is kind of, in some way, is kind of marginal and central at the same time. As a performer I don’t perform that much, I’m not involved in any band, I tend to be solo unaccompanied, which is kind of – that’s for a really desperate audience you know. So I don’t really incur – I don’t have enough life experience of band settings or band contexts, I can’t really comment on that. But my perception is certainly that if you looked at the output from Ireland in terms of live performances and recordings, it just seems to be it doesn’t add up with my perceptions of what’s out there in terms of numbers, quality and talent. However in the absence of some piece of information that we can hold up and say "It says so here" that remains an assertion. Wouldn’t it be much better if the register of female performers was in place, if we knew more on a regular basis about the programming performance of, maybe festivals, broadcasters and others, so that you have an evidence base that can then be interrogated? Because part of me is still asking the question as a male, how much of the way I think and behave in the world of music is influenced by things that predate my existence, you know, the models and the stereotypes that have been embedded in traditional and folk music from the 50s and 60s – I was born in 1961 by the way - despite the appearance! You know, so how much of that is influencing the way I consciously behave? My earliest recollections of traditional music were probably things like the Dubliners and the Clancy brothers, beer, beards, beer bellies, you know, lads. I spent an awful lot of my formative years in the company of people who were significantly older than me, of both genders, so I wasn’t really aware at that level, at that stage that there was any divide or separation of the gender participation, but clearly I now know that there is. But I would be happier and I would feel better equipped to do more if I had access to maybe more influential evidence and fact-based materials, not just stories and case studies but maybe numbers and statistics and opportunities. OK – thank you.

Lynette: I’d like to thank all our panellists for their very insightful talks this morning. Can I just gauge from the audience who has a question, who would like to contribute? Hands up, don’t be shy. OK, we’re going to get a couple so we’re going to give you another couple of minutes to think about that. I have plenty of questions, so I’ll just continue then. I’ll interrogate from the front. OK...

Peter, I want to go to you first please. You’ve mentioned diversity of thought and the role of men amongst other things in your brilliant talk this morning. Diversity of thought, that’s a huge ask, that is a massive, massive ask, how do you even attempt to tackle that practically and in a tangible way?

Peter: I don’t think ... yeah, I think it is a big ask, and you’re not looking ... I think one of the challenges, just from a business point of view, is people expect one person in an organisation to solve this, it’s never going to work. So companies go, "We’re brilliant, we just hired a head of diversity" or "We’ve got somebody who’s looking at diversity.". Rather than one person with a thousand initiatives, it’s a thousand people with one initiative. So it’s – for me, the number one thing you have to do in organisations is actually just start with this communication, and an understanding, because people just do not get it. There’s a huge amount of men out there who just do not get this, do not understand it; because of their privilege because they’ve never seen it.

Lynette: What if they don’t want to get it?

Peter: Yeah, and partly they won’t want to get it, but if they don’t want to get it you need to explain to them that there’s this idea, and sometimes there’s this zero-sum game of "Women are better, that means I’m worse, so if they can do better what am I going to do?’. Whereas what you really have to show them is - your company won’t exist. Like, that’s literally what will happen. In 10 or 15 years, anybody now who’s coming out of college has always seen the internet from the moment they’re born, they’ve never just seen this pale, male, stale senior management team. They’ve seen different cultures, different ethnicities from the moment they’re born. If in 10 years time this business hasn’t changed, nobody is going to want to join it. You don’t have a company without people. So what they need to realise is it's not a zero-sum game - if you hire or you attract more women, everybody grows. This isn’t like a finite problem, what you’re trying to do is build business. Diversity of thought is that one person can make a difference to a thousand jobs by coming up with that new idea. And as I said earlier, diversity of thought, diversity of idea - better ideas, better innovation will create more opportunities for organisations.

Lynette: And you mentioned as well though that most times when you’re giving these talks, you’re speaking to a room full of people who believe in everything you’re saying, so you’re preaching to the converted, each time, and that in itself is a huge challenge.

Peter: Yeah, because the word "diversity" is like "Oh, that must be for women!". You hear that all the time, the diversity bent is probably for women which is crazy but it is true. So firstly people start using inclusion, because they think inclusion is a nicer word than diversity in terms of getting more people involved, everybody wants to be included. But again it’s trying to ... honestly, at the beginning you often have to force men to come, because when they come they realise that this really interesting, this is actually a powerful thing for business, for life, for social ... but if they aren’t pushed to come in the first place, they’ll never get to understand it. And even in organisations, having a women’s group probably isn’t a great idea, it’s probably having gender groups or not calling it women’s groups because whether you like it or not, most men aren’t going to a women’s group because they’ll think "Well, it’s not for me." So even simple things – you know, so "Mother And Baby" groups should be called "Parent And Baby" group. So it kind of works both ways. But it’s very much skewed towards men at the moment. But it’s about just being aware of those things.

Lynette: Hmm, interesting points. Anyone else on the panel want to pick up on that? Audience? Yep there’s a lady here.

Questioner 1: I feel really anxious about saying this. Like, this is about women? And yet I’ve heard more of a male voice. And, like, men are invited here. I’d love to hear more from Eleanor, and more from you. It’s just what happened. And I think this is the unconscious bias thing, and we need to check ourselves on this all the time. And could I hear more from the women please?

Lynette: OK, well, I thought it was important to hear from the men so. Because the women tag is implied, so I apologise if that was your perception there.

Questioner 1: But it’s just my feeling.

Lynette: Absolutely, I was going to go to Liz next anyway, Liz mentioned something, well she spoke about women being kind to women, and that being a very important part of this conversation and discussion.

Liz: Yeah, I think we all have a responsibility to look after each other. Karan talks a lot about being kind and being respectful and I think that women have a responsibility to look after other women as well, to make sure that they, you know, give the hand up to other women coming behind. You know, as a lecturer I have responsibility for, you know, hundreds of students every year. I do a lot of mentoring work with a lot of them afterwards when they graduate, specifically trying to help them navigate that space that Dermot is talking about, how to take their lives in traditional music and try and move them into a professional platform. And I know it’s difficult for women making that decision to do it, because if it was any other sector you would be looking up a job advertisement, and you’d look for ... first of all you’d look what the job was, you’d look how much it paid you and you’d look where it is. But if you’re starting to look for a career in the traditional arts, you’re kind of just taking a leap of faith, and because we don’t have an infrastructure as such, you’re kind of going "Oh, I’ll kind of give it a go and see how I get on and hope for the best". And that’s kind of a blind step, that I find in my experience dealing with students, with graduates, that often the females are less committed to taking that kind of "leap of faith", they’re going "Oh, you know, maybe I can go into teaching and then I can play in the summers", because it’s safer and because you don’t have to do everything for yourself, there’s a structure, there’s the steps to take. And I think then that as the women who are out there performing and who are doing it, and who have kind-of broken through those barriers, who’ve gathered that information, who have the experience, that they then have a responsibility to come and help those, you know, that next generation who want to do it. And that’s what I mean about the women looking after the women. You know I had plenty of mentors and still do have plenty of mentors who have helped me in my career and career choices, but I have to say they’ve pretty much all been men. And I don’t say that with any great joy but that’s the reality. Some of my greatest advisors that I still go to are men, because – not because there weren’t women in that space – but because they never offered, or I never felt that I could approach them. And I deliberately make it my business to make sure that I very carefully look after the young women that are on my watch and coming after, to try and help them and to steer them in the right direction. And I think we need to be mindful of that, that we do have ... that ourselves as a group, we need to look after each other more.

Lynette: I remember someone saying years ago that there were two types of women in the workplace, those who climbed the ladder and let everyone else come up after them, and those who climbed the ladder and pulled it up after them. And unfortunately I find that to be exactly the case, and I could say that too, I’ve been mentored most by men in my job. Eleanor, do you want to take up on anything Liz said there?

Eleanor: Well, I think role models are incredibly important, I really do. And when Peter was talking there about Julia Gillard, I tour a lot in Australia, so I was very, very conscious of the sexism towards her, and now she’s gone which is sad. But you know what? Jacinda Arden is in now in New Zealand, she’s the Prime Minister of New Zealand, I don’t know if you’re aware of her, magnificent, incredible woman - who was pregnant, I think, when she was elected and has been dealing with all of this stuff, breastfeeding and going to meetings and ...

Lynette: That was news all around the world: "Female Prime Minister pregnant". So what? She’s a woman, she’s having a baby!

Eleanor: But you wonder - would you have had her, if you hadn’t had Julia Gillard? And I think that’s the importance of that. When you were talking, Liz, saying that was mostly been men who have given you your breaks - that’s true for me too, it’s mostly been men who’ve given me my breaks, but to be fair, I think it’s because it’s always been men who’ve been in a position of power. Mary Black is, of course the obvious exception to that - who’s really good, and not just to me, but to a lot of other women, she was very much - and of course the whole "Women’s Heart" thing would have helped, you know a bunch of women on the road, a lot of which nobody was going to mess up. But it has mostly been men who have given me the breaks - but I think that’s because they’ve been in a position of power. And fair play to them, because they are inclusive. Usually, you know, the people who’ve gotten me jobs - producing albums etc., it has been men. It has been other men who’ve recommended me. I think the dilemma is this: the guys that are in my ... that I play with, who know me, recommend me and are fantastic to me, and are very pro. The problem is when you’re going before somebody new, and there’s a bloke going before somebody new. And if you both call yourselves a musical director or you both call yourselves a songwriter, or you both call yourselves a producer, somehow that man is judged to be competent. Now if he goes into the studio and proves himself incompetent, that’s fine - he won’t get hired again. But as a woman, you have to go in and you’re – the preconception is that you’re incompetent, that you can’t quite play guitar, that you, you know ... and you have to prove yourself competent. Now, once you do, that’s fine in my experience, it all works out for you. But why, as a woman, do you have to prove yourself competent? And why, as a man, does he have to prove himself incompetent? It’s not a level playing field. There was a young guy, he’s very well-known, I won’t say his name because he’s a lovely guy but he saw me play at something recently and he said "Oh my God, I’d no idea you were such a good guitar player" and I said "Oh, thank you very much, that’s very kind of you" and all the rest, and then he said "You know what I mean, because there’s just, you know, a lot of female women - you know, singers out there, and you know, they’re just not great guitar players." And I went "Yeah, that’s true, yeah. There’s a lot of male singers out who aren’t great guitar players." And he laughed and he said "Yeah, OK, point taken, but you know what I mean - there’s a few really high-profile women out there who can’t play guitars.". And I’m going "Yeah, there’s a few really high-profile men out there who can’t ..." and I was ticking them off in my head, you know, and he went "Yeah, OK" and he took it on board, you know, but that’s the perception. And role models, I think, will hugely alter that, but in order to have role models you have to break the mould in the first place, so ...! One other thing I’d just like to say while I hog the microphone: J.K. Rowling, you know, when she went for a publishing deal they made her change her … she wanted to go out as "Joanne" but they said "We can’t, we can’t have a book called Harry Potter, about a ... you know, boys won’t buy it, you’ll have to be called J.K., they have to think you’re a man." Now you could say, "Oh, hold on, she should have just gone ahead and called herself 'Joanne'". But probably it wouldn’t have been as a big a seller as it was if she had called herself 'Joanne'. I think she was right to go as J.K. Rowling because now, my God, she is breaking the mould and everybody has a role model to look up to, you know.

Lynette: OK - Dermot just wants to make a brief point there, and then we’ll take more questions from the floor. Hands up there just till I get a gauge of who wants to speak, OK we’ve a good few questions, brilliant, so we’ll take this comment then we’ll go straight to the floor.

Dermot: Yeah, it was just to throw in an observation as well. There’s an equally big issue that we need to just keep on the table as well, which is the extent to which traditional music, music and the arts generally are undervalued in the Republic of Ireland by the State. So it’s great that we can get wheeled out ornamentally from time to time, but that’s being valued for a very focused purpose - usually political or diplomatic. That you cannot really check with that. And I don’t think it matters what is the gender of the incumbents of the top offices. Because has it really made any difference whether it’s been a man or a woman who’s been the Minister for Arts, the Director of the Arts Council, the Chairperson of the Arts Council or mostly the Head of Creative Ireland? I don’t think it really matters what the gender of the person is, or to be blunt what the talent is. Because there’s such a weight of, I would say, inertia that they have to push against to get recognition and value for the arts before you start talking about the stuff we’re talking about. That’s a really big problem. And I think it’s a useful, it’s useful and healthy to see that there’s been diversity in the gender in the people who’ve occupied those really, really important roles. But I would say it further highlights the extent to which our enterprise is marginalised from the core concerns of the machine that runs Ireland.

Lynette: But you’re relating to the point that Liz made there, that sometimes we’re eating ourselves - when you bring everybody with us, and move forward strategically ... and that’s just not happening at the moment. To the floor then, and we’ll go to the back first for questions. Someone at back, yourself there.

Questioner 2: It’s a question for Peter. Thanks a million for your wonderful speech, I really enjoyed it. I was wondering how your very excellent articulated points translate into trad. So, for example, if I meet a pub owner who’s going to try to figure out who’s going to be his session workers for the year ... how could I start the conversation of, "You know what? it would be really cool if there was maybe 30% women this year.". If I met a person who’s in charge of a venue, or who is in charge of a festival, and just socially have the chat with them, how could I start a conversation of "Oh my God, you know, it would be so cool to have maybe women consciously included in the list this year!" - without arousing defensiveness or a feeling of their being criticised. And finally, if I’m in a band situation or a session musician situation where I’m in the middle of a couple of people, because - actually, I’ll just be honest, all men, because it’s always all men - and they’re talking about who to get for their next gig or something, how do I plant the seed of "Oh, you know what, you might ... " ... in a very nice, or in an effective way, "How about you examine the ideas with conscious bias and you consciously try to include some girls / women / whatever?!"

Peter: Wow ...! Em ... Not easy. And it’s not easy because it just completely depends on the person you’re dealing with. And you’re trying to get over years of their own bias and views, and remember their views are 100% right because they’re their views, and this is the challenge. One of the best ways people often say is for you to have a couple of allies to help you make this point. Because when you make the point and then they challenge you on it, it’s just natural to get quite defensive. Whereas if you’ve two other people supplementing your point as well, and actually "She makes a great point here" - whether that’s a man or a woman it doesn’t matter - but often you’re actually trying to, kind-of, curry favour along the way with people who are closer to him that isn’t just you. Because it is tricky - there’s no two ways about it, no one’s going to immediately say ... so that’s the first way. And the other way is show him the benefit. 50% of your customers are female, do you not think more people may come? So think about the money signs, and the other signs. So you have to actually start by working out what are the drivers to this person. Which is tricky enough to do, but I would always say you’re better doing it with a little bit more support rather than one-on-one. Because when you're dismissed, it is really, really hard not to get defensive around it. But there’s no question about it, it’s very difficult. If they’ve always done a thing a certain way, trying to get them to change ... so the last way is giving them examples of other people maybe have changed, and how they’ve become successful because of that.

Questioner 2: Thanks, that’s great.

Lynette: Pauline, you’ve a question?

Pauline: My question is for Eleanor. I just wondered in your role in IMRO if you had seen any improvements in other territories outside of Ireland, and if so how do you think ... are other places faring better than here?

Eleanor: It’s not so much in my role with IMRO that I see it, Pauline, but I think in – I know you’ve been to the Blue Mountains ...

Pauline: I have, and it was 50/50 there, it was amazing.

Eleanor: It was 50/50 this year and everybody was commenting and a couple of guys were commenting and a couple of guys said "Oh my God, the amount of women on the Blue Mountains this year, it’s ridiculous’. It was 50/50. !

Pauline: Yeah, but it was so amazing. Because for the first time I had ever gone to a festival, and really seen music that completely interested me, inspired me, I had a complete blast, and I just walked around and I loved everything I saw and there was just women everywhere, I felt happy, I felt ... I just felt so rewarded - as a punter not as a performer. But just going around from stage to stage. But I just wondered if you’d been privy to information that we don’t know.

Eleanor: That was the most I’d ever seen. For those of you who don’t know, the Blue Mountains Folk Festival is one of the biggest folk festivals in Australia, there’s a few, there’s the National, there’s Port Fairy, and then there’s the Blue Mountain, and it’s one of the most significant and probably seen to be one of the most musically progressive as well, just ... But there’s a couple of things, I mean with regards to my role with IMRO, I do actually look at the Australians again, APRA is a particularly good operation for championing women. And I’ve had a couple of meetings with them as to how they did it, and they took an audit of their members etc. And I’m going to try and replicate what they did to some extent because they were way ahead of us to be honest. And we’re trying, we’re not ... you know, we’ve got four women on the board, but it’s a board of 15 so we’re getting there, but room for improvement. Yeah but I think the Blue Mountains was significant and again it’s a bloke who runs it, and I was chatting to him about it and I said "Did you make a conscious effort to ... you obviously made a conscious effort to pick women." and he said "Actually no, I didn’t.". He actually didn’t make a conscious effort, he said it was just what came out, he said "Some of it was coming from the people who were buying the tickets, and it’s primarily actually women who buy the tickets, it’s not necessarily women who primarily attend but the ones go booking the tickets are actually women." This is true actually of people who buy music. Music tends to be bought more by women, even if it’s for men the women do the buying in a lot of cases. So yeah - I thought that was interesting, that it wasn’t a conscious decision and yet that’s where he came to, and it was incredibly successful.

Lynette: Can I just ask Eleanor, was that governmental support they got?

Eleanor: It’s ... they would get a very small amount of government support as far as I’m aware, but it’s mostly self-funded, I mean it’s a huge festival. Now the APRA is a very good organisation in the territory. The Australian government is very supportive of the music industry - far, far more supportive than our government would be of ours. You know, they have quotas on the radio stations over there, it’s the only territory where you go to and you hear all this music in English, and it’s blues and its rock but you don’t know it. You’re thinking "Why don’t I know it?" and of course it’s because it’s all of these Australian bands.

Lynette: Whereas we have broadcasters here who congratulate themselves because they have an all-Irish playlist for one day every year. ... It’s true. ! More questions from the floor - I’ll go for this lady first.

Questioner 3: This question is for Liz. Just kind-of on a grassroots level, as an educator, how do you tackle, I suppose, giving a leg up to younger female musicians but also raising an unconscious bias with the male and female musicians at the same time?

Lynette: Did everyone hear that question?

Liz: Em, well, I mean it’s always a challenge because in ... I was in U.C.C. for years and actually while I was there, the majority of students who were in the traditional music space were female, so when I had the group "Fiddlesticks", for example, people thought it was like a female fiddle movement and actually it wasn’t, it was just the fiddle players who were students at the time and who ended up there. And currently I teach in Ulster and we’ve a smaller cohort of traditional music students, and it’s pretty much 50/50 male and female. Academia is a horrible place when it comes to gender inequality and I have few happy stories to relate on that front from either of my academic experiences. Sometimes in fact – I mean that’s kind-of at a staff level, where there’s all kinds of, you know, inequalities going. And sometimes it happens, actually, from a student level as well. I’ve had male students who’ve absolutely resisted me being in, telling them, you know, how to do things, there’s been kind of resistance sometimes in the traditional space, in a performance space, from male students - when I’m going to teach a group for example - who don’t want to hear that, or take leadership from a non-male. So yeah, so I mean over my, whatever, 20 odd years and that, there’s been all kinds of challenges. But for me, I mean I try to give my students, male and female, opportunities to practice traditional music in the professional space as much as possible. So I take them to festivals, I take them to events, where they get the chance while they’re protected, effectively - they’re still students and I’m with them. And they learn how to, you know, negotiate a deal, and how to do publicity and all that. We take them and do that. Well, they're getting an insight into it, and we get them to kind-of reflect on the situation, on the balance, on what they want, how they want to present themselves, what they’ve learned, all of that, to try and allow them to do that as part of their education journey. Because there definitely is - I mean one of the things that I’m very aware of is - all these students are coming out of Cork, out of Limerick, out of Derry, out of Maynooth, out of all these courses that offer degree status in traditional music. And where’s the impact on the sector, where are they all going? So even if people are coming out with degrees, male and female, what difference is it making to the world? Yes, we have a few new groups, but that’s not even tallying with the numbers that are kind-of walking around with this qualification in their back pockets. So where are they going? And how can we make ... how can we create opportunities to allow the women, who have those degrees, to feel that there is an opportunity there as a performer - other than falling back into the teaching arena as the only option? We still don’t have the diversity of professional opportunities well enough articulated for graduates. And we certainly don’t have the pathway into a professional performing career well enough articulated - for both male and female - but particularly for, females. And again it comes back to that thing of, like, "OK, I’ve put all this money into getting a degree, I’ve invested in this, now I want to be a performer, how do I go about it?" Big blank canvas there; that you have to start and completely climb another mountain, that you feel you have to do it all by yourself. So until we get our act together, and create those pathways to enable people to do it, either through higher education or before it - people who don’t want go down that route but still want to be performers - we really do, as a sector, need to step up and make that happen, if we want to be fully professional.

Lynette: ... and by the way, Peter, just in case you’re worried there, that’s "Willie Clancy Week" in Miltown Malbay, affectionately referred to amongst the traddies here as "Willie Week".

Éamon: Just quickly, do you think there’s any legs to putting pressure on radio and media to start acknowledging and playing more Irish music? Because, just to touch on your point Liz, like, when you go to U.L. - I took a master class a couple of times, two fellas, two girls, a completely balanced group, and I said to all of them at the end of it: "What do you want to do? What do you want to come out of college and do?" And they all shrugged their shoulders and said "Dance show, maybe ... ? ". So, like, none of them even had the ambition to go and be creative, or to go out and say, you know, "I’m going to go and start something" or "I’m going to ... " you know, there was no real juices flowing that way. They just thought, well at least we could go and do that - and that’s a real limited shelf life as well. So, like, at the end -I suppose if you’re in a rock band, you want to be on the cover of Rolling Stone and you want be playing at Glastonbury, but not every Irish musician wants to be jumping around Milwaukee, you know? So, like, is there something, is there more that we can do here, to kind of put pressure, like, on media? To kind-of play it more, or to kind-of build an audience for it at home, rather than ... ? Because it does seem that we’re all just kind-of looking around ...